FEATURE ARTICLE

The Applied Strategic Leadership Process: Setting Direction in a VUCA World

Everett Spain and Todd Woodruff, U.S. Military Academy

ABSTRACT

Strategic leadership frameworks have become more complex in response to our increasingly volatile, uncertain, complex, and ambiguous (VUCA) world. While comprehensive strategic approaches may help leaders of large bureaucratic organizations exercise control over their staff and resources, these approaches may not be optimal for all organizations and contexts. Given the acceleration of environmental volatility, complexity, and competition, we offer leader developers and aspiring strategic leaders the Applied Strategic Leadership Process (ASLP), a focused and simplified strategic leadership approach that integrates relevant scholarship and practical tools to better enable the success of strategic leaders across cultures, situations, and leadership styles. The ASLP is organized with the themes of strategic judgment, strategic influence, and strategic resilience. Strategic judgment includes assessing the external environment, assessing the internal environment, and setting strategic direction by choosing the optimal big ideas. Strategic influence includes leading the organizational change needed to accomplish the big ideas. Strategic resilience includes developing its leaders’ strategic competencies, character, and wellness while attracting and building a pipeline of junior leaders. We conclude by sharing the 10 strategic leader competencies that several modern-day senior leaders believe will be the most important to leading successfully in the future.

Keywords: Strategy, Leadership, Values, Leading Change, Leader Development

Citation: Journal of Character & Leadership Development 2023, 10: 250 - http://dx.doi.org/10.58315/jcld.v10.250

Copyright: © 2023 The author(s). This is an Open Access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/), which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original work is properly cited.

CONTACT Todd Woodruff todd.woodruff@westpoint.edu

Published: 23 December 2022

Introduction

Strategic leadership frameworks have become intricate in response to an increasingly volatile, uncertain, complex, and ambiguous (VUCA) world. While detailed strategic approaches may be useful for strategic leaders exercising control over a large staff and resources and facing multidomain global competition, they may be too unwieldy for many organizations and contexts. Ease of implementation is critical because strategic leaders in VUCA environments must gain and maintain an advantageous pace by seeing, understanding, and exploiting opportunities faster than their competitors (Dempsey, 2012). Superior speed in cycles of strategic decision-making and leading change are akin to military strategist John Boyd’s idea that decision-making pace provides competitive advantage by executing the “observe-orient-decide-act (OODA) loop” faster than one’s competitors (Boyd, 1995; Dempsey, 2012). Given the acceleration of environmental volatility and complexity and the need for faster strategic action, we believe the appropriate response is a simplified strategic leadership process that operates across cultures, situations, and leadership styles. As such, we offer a streamlined, applied strategic leadership process (ASLP) that is accessible to aspiring strategic leaders. This method is currently used within the Eisenhower Leader Development Program, a joint graduate program run by West Point and Teachers College, Columbia University, to educate today’s leader developers and tomorrow’s strategic leaders. The framework has the potential to add value across a range of mid- to senior-level leader education programs and by organizations seeking clarity and parsimony in their strategic leadership processes.

Prior to defining effective strategic leadership, we must first understand the meaning of both strategy and leadership. Merriam-Webster (1983) defines strategy as “the art of devising or employing plans or stratagems towards a goal.” Informing their seminal model of organizational change, management scholars Burke and Litwin (1992) define strategy as the process by which an organization achieves its purpose over an extended period. Economists Froeb et al. (2015) define strategy as the steps to gain sustainable competitive advantage. We define strategy as the plan to get from the current reality to the envisioned future, all while operating in a competitive environment.

The U.S. Army defines leadership as “the activity of influencing people by providing purpose, direction, and motivation to accomplish the mission and improve the organization” (ADP 6-22, 2019). John Maxwell (2007) defines it as “influence” and Ron Heifetz et al. (2009) defines it as “mobilizing people to tackle tough challenges and thrive.” Leadership includes motivating followers to achieve group goals while emphasizing organizational functions such as strategy and systems (Kaiser et al., 2012).

By integrating the meanings of strategy and leadership, we define strategic leadership as determining where an organization needs to go to achieve sustainable competitive advantage and getting it there. Recognizing that firms are at risk of going out of business, non-profits are at risk of losing their access and funding streams, and nations are at risk of being conquered, strategic leadership includes the major decisions and direction setting likely to have existential consequences, where day-to-day leadership and management does not.

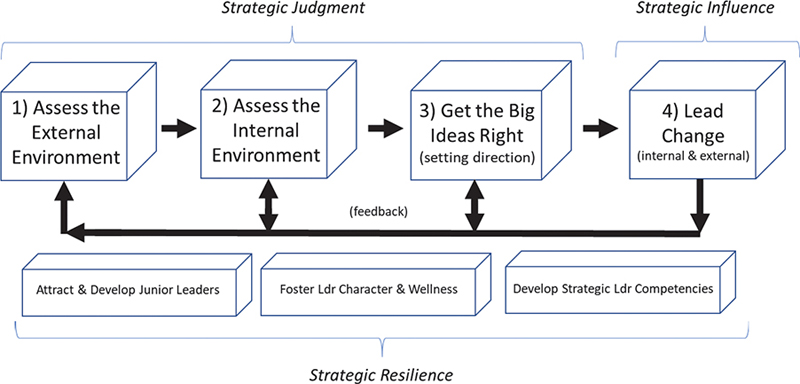

The ASLP flows from this definition and includes the themes of strategic judgment—assessing the external environment, assessing the internal environment, and setting direction by deciding on the optimal big ideas; strategic influence—leading the organizational change needed to accomplish the big ideas; and strategic resilience—developing its leaders’ strategic competencies, character, and wellness while attracting and building a talent pipeline of junior leaders (see Figure 1).

Figure 1

The Applied Strategic Leadership Process (ASLP).

Though the ASLP’s four steps within the themes of strategic judgment and strategic influence are presented in a linear stepwise progression, they certainly overlap in concept and reality. Additionally, strategic leaders should revisit each step when exogenous shocks occur or when competitive dynamics are altered. Lastly, strategic leaders should always adapt the ASLP to best leverage the idiosyncrasies of the leader, the organization (and its people), and the external environment.

Strategic Judgment

ASLP Step 1: Assess the External Environment

Lewin’s seminal theory on behavior (1936) explains a person’s behavior is a function of both that person and his or her environment. The organizational equivalent to Lewin’s theory would be that organizational-level behavior is a function of its strengths and weaknesses (internal assessment) and its environment (external assessment).

Before making decisions of strategic consequence, leaders applying the ASLP should comprehensively assess their external environment. In fact, the Burke-Litwin model asserts that the external environment, more than any other factor, drives the need for and nature of organizational change (Burke & Litwin, 1992). Observing the local, national, and global news cycle clearly illustrates how strategic leaders must be able to recognize and lead their organizations through a complex array of forces outside of their control, including the effects of pandemics, disruptions to global supply chains, cultural/political/social/technological megatrends, economic interdependence, artificial intelligence, and the ubiquity of data.

Additionally, strategic leaders should also understand competitive externalities. Porter’s Five Forces (2008) offers a steady lens to do so and has been broadly accepted across academe and industry. These include rivalry among existing competitors, power of suppliers to drive up costs, power of buyers (customers) to drive down revenue, threats of substitutes, and threats of new entrants. Though the five forces were designed to be used to assess a competitive business environment, they can readily be adapted to a national-security, U.S. government agency, educational institution, or non-profit analysis. Indeed, a previous study demonstrated that applying the five forces enabled a comprehensive assessment of the maritime security environment (Yetkin, 2013). Strategic leaders should ultimately use the tools they find effective and are most comfortable with. The key is that they understand the external environment and how observable changes are creating opportunities and threats for their organization.

Additionally, a strategic leader could initiate a strength, weaknesses, opportunities, and threats (SWOT) analysis, which integrates both ASLP Step 1 (SWOT’s opportunities and threats) and Step 2 (SWOT’s strengths and weaknesses, discussed in this paper’s next section). With its four lenses, the SWOT matrix is meant to simplify the complex, dynamic internal and external environment of a competitive organization (Mintzberg, 1994).

ASLP Step 2: Assess the Internal Environment

After assessing the external environment, strategic leaders should assess their organizations’ internal environment. A systematic way to examine strengths and weaknesses is to assess each of the Burke-Litwin model’s internal dimensions of management practices, organizational culture, climate, systems, structure, task and skills, and individual needs and values. The wisdom of other prominent scholars can be used to complement this framework. For example, strategic leaders can assess their organizational culture by applying Edgar Schein’s (1990) framework of artifacts, espoused values, enacted (in-use) values, and underlying assumptions. Alternatively, they can apply Tushman and O’Reilly’s Congruence Model (2002) to examine the alignment of their big ideas with their organization’s capabilities of its people (human capital), structure (formal organization), culture, and nature of the work (systems). These internal-focused frameworks will allow leaders to assess if their organization can accomplish its current and future strategies within its competitive environment.

ASLP Step 3: Get the Big Ideas Right (Setting Direction through Deliberate Decision-Making)

The analysis and assessment of the organization’s external and internal environments will likely identify emerging opportunities and threats with strategic implications for the organization. Strategic leaders visualize these emerging opportunities and threats through the lens of their core organizational values to set the organization’s strategic direction through the creation of a vision (the big ideas) and making decisions of long-term consequence. Examples of these types of decisions include selection on where and how a firm will compete, where an army will commit its main forces in battle, and which major services a non-profit will provide and where. In short, these decisions set the direction of the entire organization and serve as the basis from which most other decisions and actions flow.

The ASLP’s third step expands on and operationalizes the Burke-Litwin model’s mission and strategy, organizational culture, and leadership dimensions. Knowing that there is a field of management research dedicated to decision-making sciences, our process suggests several options for decision-making, including the recommend, agree, perform, provide input, and decide (RAPID) and deciders, advisors, recommenders, and execution stakeholders (DARE) approaches, which clarify who does what, and the rational decision-making approach, which is focused on process and informed by the organization’s core values and an ethical decision-making tree.

RAPID, developed by Bain & Company (2011), is a way to assign roles and accountability in the decision process. It helps clarify who provides input to a decision, who shapes the decision, who makes the final decision, and who executes the decision. DARE, developed by McKinsey & Company (2022), identifies the decision maker and decision stakeholders/contributors and promotes delegating and empowering others to make all but the most critical or strategic decisions. Both approaches accelerate the decision-making process by clarifying who does what and enable strategic leaders to focus on getting the big ideas right.

The rational decision-making process includes understanding the problem, generating alternative solutions, analyzing and testing competing solutions, and choosing a course of action (Shattuck et al., 2017). Informed by the ASLP’s assessment of the external and internal environment, the rational decision-making process continues as the strategic leaders leverage their organization to generate and deliberately analyze their courses of action against measurable evaluation criterion.

When working through the rational decision-making process, wise strategic leaders will always check themselves (or ask a trusted colleagues to check them) for personal cognitive biases, actively solicit others’ input, and pre-test potential courses of action by putting it through an ethical decision-making tree (Shattuck et al., 2017). The ethical decision-making tree asks three questions, (1) Is the proposed course of action legal? (2) Does it serve important organizational interests? and (3) If I do it (or do not do it), would it violate others’ rights or my responsibilities as a person or leader? Strategic leaders should always reexamine potential courses of action that display one or more “red flags” of being against a stakeholder’s recommendation, potentially made with personal bias, or violating the ethical decision-making tree.

Though it is required for strategic decisions to be both rational and ethical, it is not sufficient. Strategic direction and decisions must also flow from the organization’s espoused values, with those same values being reinforced by the decision and its implementation. This requires organizations to select and develop leaders with integrity early in their careers and continue that development throughout their tenures, which this paper will discuss later.

Strategic Influence

ASLP Step 4: Lead Change (Internal and External)

Steps 1–3 represent a leader’s strategic judgment and serve to create an optimal strategy. With the big ideas set for this decision cycle, a strategic leader’s fourth and final step is to lead the internal and external changes needed to accomplish the big ideas, which operationalizes the ASLP’s theme of strategic influence.

Leading change is a complex task made more challenging because problems manifested in one area (e.g., systems) may be the consequence of problems or misalignment in another area (e.g., structure). Strategic leadership scholar Doug Waters (2019) writes that a strategic leader needs the ability to influence and change the political, cultural, and economic systems that impact the organization. To enable success of planned internal change, an effective strategic leader must first influence the world around the organization to help facilitate, or at least not overly resist, the desired internal change. The strategic leader must also address the internal gaps that could prevent the accomplishment of these big ideas (Tushman et al., 2002).

To lead these external and internal changes, the ASLP suggests using Kotter’s eight-Steps for leading change (1995) and Schein’s Embedding and Reinforcing Mechanisms for changing organizations (1990). Kotter’s eight-Steps are designed to be applied sequentially, and they include (1) establishing a sense of urgency, (2) forming a powerful guiding coalition, (3) developing a vision, (4) communicating the vision, (5) empowering others to act on the vision, (6) planning for and creating short-term wins, (7) consolidating improvements and producing more change, and (8) institutionalizing the new approaches within the culture.

Schein’s five embedding mechanisms give strategic leaders levers to pull to enable the organization to pivot and include leader attention, measurement, and control; reactions to critical incidents; deliberate role modeling; criteria for reward allocation; and criteria for recruitment selection, and retention. Schein’s five reinforcing mechanisms enable strategic leaders to lock in the pivot after it is made and include organizational design and structure; organizational systems and procedures; design of physical space; stories, myths, legends, and parables; and formal statements about organizational philosophy.

Strategic Resilience

When done well, the ASLP can enable an organization to see its competitive environment, see itself, develop its big ideas, and get to where it needs to go. Yet without the strategic resilience needed to sustain the strategic leaders’ ability to keep their organizations on the right path in a complex environment or to adjust strategically in the future, organizations are at significant risk of future failure. To achieve strategic resilience, organizations must attract and develop their junior leaders, foster their senior leaders’ character and wellness, and develop their leaders’ strategic competencies.

Attract and Develop Junior Leaders

Organizations must attract and develop junior leaders so they will be present and ready to fill the strategic leader roles needed in the future. Developmental organizations focus on all talent management stages for their junior leaders, including recruiting, assessing, onboarding, developing, employing, and retaining talent. The U.S. Army does the developing thread well through its formal officer education schools (OES) program, where it gathers and trains each annual cohort of leaders (officers) for a four- to ten-month in-residence professional development course approximately every five years. As part of this effort to attract and build junior leaders, a strategically minded organization will create deliberate and comprehensive leader selection processes to objectively choose which of its leaders are most prepared to advance to senior leadership such as the U.S. Army’s new battalion and brigade commander assessment programs (Spain, 2020). Additionally, it will provide those leaders with the coaching and mentorship needed to be effective in their more senior leadership roles (Woodruff et al., 2021).

Foster Leaders’ Character and Wellness

Strategic leaders’ ability to stay morally centered and healthy is critical to their ability to lead their organizations toward maintaining competitive advantage. The increased stress and temptation often experienced by senior leaders combine to create situations where senior leaders are susceptible to failing in character, which can result in significant negative ripple effects felt by their organization and people (Ludwig & Longenecker, 1993). Organizations who actively care for their leaders’ physical and emotional health while consistently developing their character through formal courses, deliberate mentorship, and individual study can keep their leaders more healthy, resilient, and thus less susceptible to these potential pitfalls (Spain et al., 2022).

Develop Leaders’ Strategic Competencies

Effective strategic and high-potential leader development programs are based on the assessed needs of their leaders, teams, and organizations (Riggio, 2008). Knowing there is an almost endless list of competencies desired in our strategic leaders, we recently questioned six highly successful leaders who were responsible for the strategic direction of global and national-level organizations to identify what competencies are most essential to leading strategically in today and tomorrow’s complex competitive environments. Between them, they have effectively led armies in combat theaters, Fortune 50 companies, U.S. Cabinet-level agencies, and nationally renowned non-profit organizations.1 Their perspectives informed the development of the ASLP.

We consolidated their perspectives into 10 competencies essential for strategic leaders of the future. We then ranked seven of them in order of importance (with the first being most essential) and identified the other three as underlying enablers of the others’ success. The seven direct competencies include learning agility, spanning organizational boundaries, thorough decision-making process, innovation, building high-performing teams/culture, interpersonal influence, and forthrightness. The three strategic enablers included developing values and wellness, embracing diversity, and actively attracting and developing junior leaders. We describe their 10 strategic competencies above (see Table 1).

Direct Competencies

Learning agility is a strategic leader competency that includes fluid intelligence, openness, curiosity, lifelong learning, cognitive ability, digital fluency, and propensity to use big data and analytics (Mitchinson et al., 2012). Confirming the importance placed on learning, Burke and Church found that leader learning has a powerful impact on managing change (1992) while Yukl and Mahsud (2010) found that flexible and adaptive leadership is increasingly important for most organizations as change and volatility accelerate. In the ASLP, learning agility enables strategic leaders across all four steps. When strategic leaders analyze their internal and external environments, they would be wise to remember that their perspectives are both informed and limited by their experiences. Therefore, a strategic leader needs learning agility, an active and prudent imagination, and dedication to question their beliefs in pursuit of testable hypotheses.

The ability to span organizational boundaries is a strategic competency that includes political skill, consensus building, and networking ability. The strategic leaders’ ability to coordinate and direct actions across many boundaries has become an increasingly important capability for the success of large organizations. As a start point, leaders can apply the Schotter et al. model for effective boundary spanning in global organizations (2017). In the ASLP, the ability to span boundaries most enables strategic leaders in Step 1, Assess the External Environment and Step 4, Lead Change.

Establishing a thorough decision-making process is essential for strategic leaders. Strategic leaders often operate in public view, as their decisions have significant consequences for the organization, its people, and the competitive marketplace. Therefore, strategic leaders should be communicative, objective, factual, and reflective. They should strive to clarify the process for how their organizations will make decisions, including how information is sought, who is responsible for what, how decisions will be made, and provide timelines for decision points. Essential in this process is how decisions are assessed against organizational values and how stakeholders such as employees can submit ideas to the decision makers and contribute to the organization’s collective intelligence. Though this competency directly aligns with ASLP Step 3, sharing the entire ASLP with an organization’s stakeholders can help facilitate its successful execution.

Innovation is the ability to produce something new and useful by using disciplined creativity and sustained organizational performance (Smith & Tushman, 2005). Disciplined innovation includes an empirical and qualitative ability to assign probabilities to things and phenomena that were previously unknown or unpredicted (Scoblic, 2020). In the ASLP, innovation fuels the strategic leaders’ analysis of the external and internal environments to identify emerging opportunities and intrepid decision-making in Steps 1–3. Strategic leaders do not depend exclusively on their previous experiences, they also imagine the range of possibilities that face the organization, whether the opportunity flows from the organization itself (e.g., develops new proprietary technology that disrupts competition) or the external environment (e.g., a global pandemic that disrupts the existing dominant products and services).

Building high performing teams and cultures is an interpersonal competency that includes promoting a competitive team spirit (winning with honor) and the organizational resiliency to bounce back from setbacks and most directly supports strategic leaders in Step 4. This competency is also the primary outcome of the Burke-Litwin model, which provides insight for how leadership affects organizational performance.

Interpersonal influence is a competency that includes emotional intelligence, social skill, negotiations skills, interpersonal affability, oral and written communication skill, and the ability to lead up. In the ASLP, interpersonal influence most enables strategic leaders in Step 4, Lead Change. Indeed, strategic leaders can use interpersonal influence to create transformational effects (Feinberg et al., 2005).

Forthrightness is an interpersonal competency that includes character, courage, trust, humility, conscientiousness, and commitment to the organization. In our process, forthrightness most enables strategic leaders in Step 3, Getting the Big Ideas Right, and Step 4, Lead Change.

Enabling Competencies

Engaging in character development (including personal wellness) activities is a strategic competency that includes developing and displaying the grit, hardiness, and resilience to not only survive, but to thrive in a high-stress strategic leadership role. Studies of elites, which include many strategic leaders, found them to display incredible levels of resilience and stamina (Snook & Khurana, 2015). Without this hardiness, strategic leaders will not be able to effectively keep up with the incredible demands on their time and attention, and the organization will likely suffer.

Leveraging diversity is an enabling competency that includes global citizenship and cross-cultural expertise. In our process, leveraging diversity creates strategic resiliency through the creation of a diverse strategic leader talent pipeline. Additionally, strategic leaders shape organizational values that enable organizations to gain and benefit from both informational and experiential diversity, potentially improving strategic decision-making (Dunphy, 2004). Moreover, organizations that celebrate and fully include and empower underrepresented groups have been shown to be more moral and profitable (Gipson et al., 2017; Waclawski et al., 1995).

Finally, actively recruiting and developing other leaders is a technical competency that fills the organization’s leadership pipeline. The requirements for a strategic leader are so vast and complex that an organization that fails to assess and develop strategic leader competencies in its junior leaders is destined for future failure in a highly competitive, unpredictable environment. Strategic leaders seeking actionable steps to leverage this competency can begin with “Advances in leader and leadership development: A review of 25 years of research and theory” (Day et al., 2014) as they chart a path forward. As strategic leaders create and implement their recruitment and development programs, in addition to developing the aforementioned strategic competencies, they should always garner input from those high-potential junior leaders they are seeking to develop and retain.

Conclusion

In the context of our VUCA world, the ASLP provides senior organizational leaders with a roadmap to assess their external and internal environments, set strategic direction by choosing the right big ideas, and lead the change needed to get there. Looking beyond short- and medium-term impacts, the ASLP posits that organizations that develop their leaders’ strategic competencies, facilitate their leaders’ character and v more likely to be able to maintain their hard-won sustainable competitive advantages into the deep future.

Acknowledgement

The opinions expressed in this paper are those of the authors and do not reflect those of USMA, the Army or DoD. This submission does not include human subject research.

References

| Army leadership and the profession (ADP 6-22). (2019). Center for the Army Profession and Leadership, Mission Command Center of Excellence, United States Army Combined Arms Center. Army Publishing Directorate. Retrieved from https://armypubs.army.mil/ |

| Bain & Company. (2011). RAPID®: Bain’s tool to clarify decision accountability. Retrieved from https://www.bain.com/insights/rapid-tool-to-clarify-decision-accountability/ |

| Boyd, J. (1995). The essence of winning and losing. Presentation. Retrieved from https://www.danford.net/boyd/essence.htm |

| Burke, W. W., & Church, A. H. (1992). Managing change, leadership style, and intolerance to ambiguity: A survey of organization development practitioners. Human Resource Management, 31(4), 301–318. https://doi.org/10.1002/hrm.3930310403 |

| Burke, W. W., & Litwin, G. H. (1992). A causal model of organizational performance and change. Journal of Management, 18(3), 523–545. https://doi.org/10.1177/014920639201800306 |

| Day, D. V., Fleenor, J. W., Atwater, L. E., Sturm, R. E., & McKee, R. A. (2014). Advances in leader and leadership development: A review of 25 years of research and theory. Leadership Quarterly, 25(1), 63–82. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.leaqua.2013.11.004 |

| Dempsey, M. (2012). Mission command white paper. US Government Printing Office. Retrieved from https://www.jcs.mil/Portals/36/Documents/Publications/missioncommandwhitepaper2012.pdf |

| Feinberg, B. J., Ostroff, C., & Burke, W. W. (2005). The role of within- group agreement in understanding transformational leadership. Journal of Occupational and Organizational Psychology, 78(3), 471–488. https://doi.org/10.1348/096317905X26156 |

| Dunphy, S. M. (2004). Demonstrating the value of diversity for improved decision making: The “wuzzle-puzzle” exercise. Journal of Business Ethics, 53(4), 325–331. https://doi.org/10.1023/B:BUSI.0000043495.61655.77 |

| Froeb, L. M., McCann, B. T., Ward, M. R., & Shor, M. (2015). Managerial economics (5th ed.). Cengage Learning. |

| Gipson, A. N., Pfaff, D. L., Mendelsohn, D. B., Catenacci, L. T., & Burke, W. W. (2017). Women and leadership: Selection, development, leadership style, and performance. The Journal of Applied Behavioral Science, 53(1), 32–65. https://doi.org/10.1177/0021886316687247 |

| Heifetz, R., Grashow, A., & Linsky, M. (2009). The Practice of Adaptive Leadership: Tools and Tactics for Changing Your Organization and the World. Harvard Business Press, 19. https://doi.org/10.1002/bl.51 |

| Kaiser, R. B., McGinnis, J. L., & Overfield, D. V. (2012). The how and the what of leadership. Consulting Psychology Journal: Practice and Research, 64(2), 119. https://doi.org/10.1037/a0029331 |

| Kotter, J. P. (1995). Leading change: Why transformation efforts fail. Harvard Business Review, 73(2), 59–67. |

| Lewin, K. (2013). Principles of topological psychology. Read Books Ltd. |

| Ludwig, D. C., & Longenecker, C. O. (1993). The Bathsheba syndrome: The ethical failure of successful leaders. Journal of Business Ethics, 12(4), 265–273. https://doi.org/10.1007/BF01666530 |

| Maxwell, J. C. (2007). The 21 irrefutable laws of leadership: Follow them and people will follow you. HarperCollins Leadership. Retrieved from http://dspace.vnbrims.org:13000/xmlui/bitstream/handle/123456789/4802/the_21_irrefutable_laws_of_leadership.pdf?sequence=1 |

| McKinsey & Company. (2022). If we’re so busy, why isn’t anything getting done? Retrieved from https://www.mckinsey.com/capabilities/people-and-organizational-performance/our-insights/if-were-all-so-busy-why-isnt-anything-getting-done |

| Merriam-Webster’s Collegiate Dictionary, Ninth Edition (C9). (1983). Frederick C. Mish et al. Springfield, Merriam-Webster. Retrieved from https://www.merriam-webster.com/dictionary/strategy |

| Mintzberg, H. (1994). The rise and fall of strategic planning. Free Press. |

| Mitchinson, A., Gerard, N. M., Roloff, K. S., & Burke, W. W. (2012). Learning agility: Spanning the rigor–relevance divide. Industrial and Organizational Psychology, 5(3), 287–290. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1754-9434.2012.01446.x |

| Porter, M. E. (2008). The five competitive forces that shape strategy. Harvard Business Review, 86(1), 25–40. Retrieved from https://www.academia.edu/download/49313875/Forces_That_Shape_Competition.pdf#page=25 |

| Riggio, R. E. (2008). Leadership development: The current state and future expectations. Consulting Psychology Journal: Practice and Research, 60(4), 383. https://doi.org/10.1037/1065-9293.60.4.383 |

| Schein, E. H. (1990). Organizational culture (Vol. 45, No. 2, p. 109). American Psychological Association. Retrieved from https://www.researchgate.net/profile/Ronald-Riggio/publication/232551601_Leadership_development_The_current_state_and_future_expectations/links/00b4953441016cb47a000000/Leadership-development-The-current-state-and-future-expectations.pdf |

| Schotter, A. P., Mudambi, R., Doz, Y. L., & Gaur, A. (2017). Boundary spanning in global organizations. Journal of Management Studies, 54(4), 403–421. https://doi.org/10.1111/joms.12256 |

| Scoblic, J. P. (2020). Learning from the Future: Essays on Uncertainty, Foresight, and the Long Term (Doctoral dissertation). Harvard Business School. |

| Shattuck, L., Rowen, C., & Bell, B. (2018). The leader of character’s guide to the science of human decision making. In Smith, Swain, Brazil, Cornwell, Britt, Bond, Eslinger, and Eljdid (Eds.), West Point Leadership. Rowan Technology Solutions. |

| Smith, W. K., & Tushman, M. L. (2005). Managing strategic contradictions: A top management model for managing innovation streams. Organization Science, 16(5), 522–536. https://doi.org/10.1287/orsc.1050.0134 |

| Snook, S., & Khurana, R. (2015). Studying elites in institutions of higher education. In K.D. Elsbach & R. Kramer (Eds.), Handbook of qualitative organizational research (pp. 86–97). Routledge. |

| Spain, E. S. (2020). Reinventing the leader-selection process: The US army’s new approach to managing talent. Harvard Business Review. November-December 2020 (pp. 78–85). Retrieved from https://hbr.org/2020/11/reinventing-the-leader-selection-process |

| Spain, E. S., Matthew, K. E., & Hagemaster, A. L., (2022). Why Do Senior Officers Sometimes Fail in Character? The Leaky Character Reservoir. Parameters, 52(4), 117–138. https://doi.org/10.55540/0031-1723.3190 |

| Tushman, M., Tushman, M. L., & O’Reilly, C. A. (2002). Winning through innovation: A practical guide to leading organizational change and renewal. Harvard Business Press. |

| Waclawski, J., Church, A. H., & Burke, W. W. (1995). Women in organization development. Journal of Organizational Change Management, 8(1), 12–22. https://doi.org/10.1108/09534819510077092 |

| Woodruff, C. T., Lemler, R., & Brown, R. (2021). Lessons for leadership coaching in a leader development intensive environment. The Journal of Character & Leadership Development, 8(1), 50–65. Retrieved from https://www.usafa.edu/app/uploads/JCLD-Winter2021_web_final.pdf |

| Waters, D. (2019). Senior Leadership Competencies. In Galvin & Watson (Eds.) Strategic Leadership Primer for Senior Leaders (4th ed., pp. 61–72). US Army War College. Retrieved from https://apps.dtic.mil/sti/pdfs/AD1124820.pdf |

| Yetkin, U. (2013). Revealing the change in the maritime security environment through Porter’s five forces analysis. Defence Studies, 13(4), 458–484. https://doi.org/10.1080/14702436.2013.864504 |

| Yukl, G., & Mahsud, R. (2010). Why flexible and adaptive leadership is essential. Consulting Psychology Journal: Practice and Research, 62(2), 81. https://doi.org/10.1037/a0019835 |

Footnote

1 These interactions took place in 2019 as part of designing the semester-long 3.0 credit-hour course LD730: Strategic and Cross-cultural Leadership, taught by the authors in West Point’s masters-level Eisenhower Leader Development Program. The perspectives were provided by strategic leaders whose collective experiences include serving as secretaries of U.S. Cabinet agencies, CEOs of Fortune 50 companies, 4-star military leaders of the US Department of Defense combatant commands, and as the senior psychologist of a major U.S. national security organization.