FEATURE ARTICLE

A Strategic Organizational Approach to Developing Leadership Developers

Celeste K. Raver, United States Naval Academy

Andrew K. Ledford, United States Naval Academy

Michael Norton, United States Naval Academy

Abstract

In leadership development, the emphasis is often on the direct development of the individual, focusing on the individual’s development as a leader or on skills to deal with the process of leadership. However, less attention is paid to developing those that develop the leaders—the leadership developers. This article provides two frameworks to consider in developing leaders through a layered approach focused on leadership developers rather than simply those that are being developed. The first framework highlights the levels of leadership development within an organization: the emerging leaders, those that develop the leaders—leadership developers, and those that develop the leadership developers—leadership tutors. All levels require cognitive understanding of the necessary leadership concepts—knowing, behavioral patterns that foster success—doing, and cultivation of affective qualities of “being a leader.” The article highlights how the experiential learning cycle serves as a foundation for both leader and leadership development as it enables emerging leaders to grow in the domains of knowing, doing, and being a leader and gaining leadership skills. The article further highlights how leadership developers support the development of emerging leaders by actively engaging the experiential leader cycle. The second framework links the experiential learning cycle with a deliberately developmental organization focused on continued growth of those within the organization relative to core leader and leadership competencies. The deliberately developmental leadership organization utilizes principles embedded into the culture of the organization, practices enacted by all in the organization, and community to robustly form successful leaders.

Citation: Journal of Character & Leadership Development 2023, 10: 253 - http://dx.doi.org/10.58315/jcld.v10.253

Copyright: © 2023 The author(s). This is an Open Access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/), which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original work is properly cited.

CONTACT Michael Norton luning@usna.edu

Published: 23 December 2022

Introduction

Leadership can’t be taught. Leaders are born, not made. The only way to learn leadership is at the school of hard knocks. These myths of leadership development still exist today despite decades of study that demonstrate they are in reality, myths. The science of leadership development is ongoing and increasingly revealing leadership as complex, occurring through a social dynamic process (Hollander, 2009; Wallace et al., 2021). In the process of leadership, there is an interaction that takes place between the leader, the followers, and the context of the leadership situation (Avolio, 2007; Silva, 2016). For decades, leadership development programs have tried to enhance leaders and improve their ability to navigate this social dynamic process. However, no singular solution has abounded, and leadership development programs have fallen short due to a gap between leadership theory and practice (Day & Thornton, 2017), allowing the myths to persist.

There is agreement that to develop a well-rounded leader, leadership development programs must focus on both the advance of the person, the leader, as well as pedagogy regarding the leadership process (Day et al., 2009; Lunsford & Brown, 2017). However, this focus on both the leader and social dynamic process of leadership alone does not develop expert leaders (Day & Thornton, 2017). Over the last decade, a more holistic approach to the complexities of leadership development has begun. Researchers have suggested that leadership development programs should concentrate on cognitive, behavioral, and affective development (Kolditz et al., 2021; Wallace et al., 2021). Others have highlighted how leadership development must take place over time, where long-term development only occurs with deliberate and dedicated practice (Day & Dragoni, 2015). Recent research proposes the importance of a deliberately developmental organization (DDO) approach to leadership development (Kegan & Lahey, 2016). A DDO embeds an enriching and holistic approach within the culture of the organization.

To establish a culture that fosters this continuous development, there must be an emphasis on developing both the target audience—the emerging leaders—as well as the key influencers that will have an impact on the target audience. Yet, leadership development programs and organizations focus almost exclusively on developing the target audience. Little emphasis is placed on developing the individuals—leadership developers—who have an impact on the emerging leaders. Leadership developers are those who serve in both formal and informal roles to develop future and emerging leaders’ cognitively, behaviorally, and affectively through both short-term and long-term interactions.

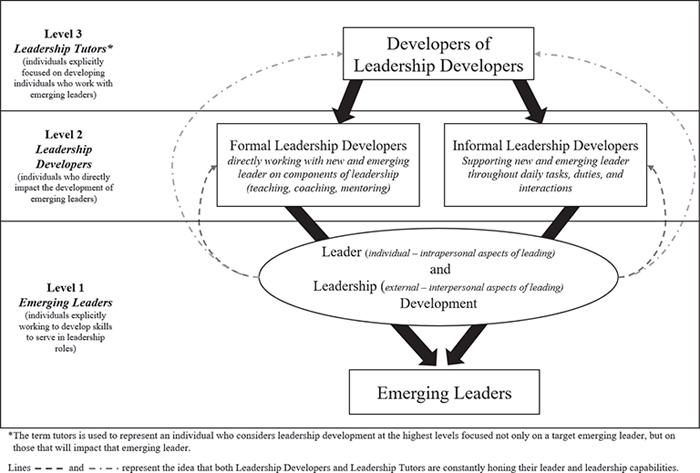

This article will begin to address these gaps by providing a framework to think of leadership development through a multilayered approach focused on the target audience—the emerging leaders—those that develop the leaders—the leadership developers—and those that develop the leadership developers—the leadership tutors. This framework requires a consideration of the multiple levels of leadership development, which are presented in Figure 1. In the model, Level 1 entails the emerging leaders, where development of both the leader at the individual (intrapersonal) and leadership (interpersonal) level can be achieved with a focus on building specific competencies. Level 2 incorporates those that formally and informally serve to develop emerging leaders, referenced as leadership developers. Level 3 holds the leadership tutors; those that dedicate time explicitly to developing the leadership developers. One important component in the model is that leadership development is perpetual. Thus, leadership developers and leadership tutors must continuously focus on their own leader and leadership competencies to avoid stagnation. This article will first highlight developmental approaches that should inform the development of leaders. Then, using the model presented in Figure 1, the article will build a framework for a multilayered approach for leadership development focused on both the emerging leaders and the leadership developers.

Figure 1

Levels of Leadership Development.

Approaches to Development

Domains of Learning

An approach to development in general that applies equally to leadership development incorporates three domains of learning: the cognitive, behavioral, and affective (Anderson & Krathwol, 2001; Bloom et al., 1956). Development across these domains ensures complete understanding of the concept being taught (knowing), deliberate practice (doing), and personal integration of the idea into how one operates (being). The cognitive domain contains the intellectual development—knowing (Bloom et al., 1956). In this domain, there are six levels which range from basic awareness of a certain idea (remembering) to being able to synthesize and generate new ideas based on the underlying knowledge of a concept. In the development of leaders, this knowing, or the cognitive domain, must be integrated into the developmental process to ensure the individual has foundational knowledge about components of human behavior (both their own and others) and the dynamics of teams, organizations, and society that impact leadership effectiveness (Day & Zaccaro, 2004; Kolditz et al., 2021).

The behavioral domain describes psychomotor functions—doing (Harrow, 1972). In this domain, the emphasis is on physically accomplishing tasks, performing movements, and skills; the highest level is a mastery of the skills. Leadership is inherently an active endeavor; it requires a leader to respond to others and the situation in which one is immersed. Leaders must do; they cannot passively allow the world to shift around them. Thus, leadership development should include a focus on doing activities associated with leading. In other words, effective leadership development programs incorporate a focus on the behavioral domain of learning (Brown, 2022; Kolditz et al., 2021; Wallace et al., 2021).

The affective domain entails emotions and attitudes—being (Bloom et al., 1956). Development in this domain enables individuals to move from lower processing of emotions to higher processing (placing value on ideas which enable an individual to find solutions to intrapersonal or interpersonal issues) (Krathwohl et al., 1964; Pierre & Oughton, 2007). In general, the ability to process information at more complex levels and in turn respond to the world centers on internalization which is central to development in the affective domain (Hoque, 2016). One progresses through the affective domain of learning with an internalization process where comprehension of an emotion goes from general awareness to a value that guides or controls behavior. For leadership development, the affective domain—being—is central to one’s growth as a leader (Kolditz et al., 2021). Much of leading centers on awareness of one’s emotions, which become internalized into the leader’s values that then serve to guide the leader in responding to situations (Wallace et al., 2021). Thus, leadership development programs are remiss if they do not focus on the affective—being—aspects of leading.

Although each of the domains has a specific focus, learning activities can certainly overlap. One of the ways to magnify and capitalize on this overlap is to combine the domains of learning with other developmental approaches, such as the experiential learning cycle (Kolb, 1984). There is support to suggest developmental approaches that combine the learning domains with experiential learning lead to higher level cognition, psychomotor acumen, and affective capabilities (Bergsteinera & Avery, 2014; Simm & Marvell, 2015).

Developmental Approach

Experiential learning theory lays out a holistic learning process which enables individuals to learn, grow, and develop complex capabilities (Kolb et al., 2014). There are four components of the learning cycle: concrete experience, reflective observation, abstract conceptualization, and active experimentation (Kolb, 1984). Concrete experience involves having an experience; the behavioral domain of learning, and at times the cognitive depending on the experience, is engaged during this phase. This experience generates emotions. Reflective observation centers on analyzing the emotions generated by the experience, reflecting upon the experience or engaging the affective domain of learning. Abstract conceptualization moves to thinking about the experience which generates learning, which involves both the affective and cognitive domains. Finally, during active experimentation, one tries out what they have learned engaging the behavioral domain through doing.

Experiential learning can serve as a foundation for leader and leadership development programs (Guthrie & Bertrand Jones, 2012; Huey et al., 2014). Relative to leadership, an example of the experiential learning cycle can be seen on the athletic field with the team captain pushing the members of the team to peak performance. As the team has a concrete experience, losing against a team they should have beaten, for example, the team captain reflects on what she or he observed, formulates a concept of why it happened, and then draws conclusions. The team captain then actively experiments with ways to address the conceptualization that mitigates the problem in the hopes of a more positive future experience, the team winning their next game. This cycle continues in the hope of optimizing behavior for optimal performance.

The experience learning theory is used in leadership development at service academies, such as the U.S. Naval Academy (Huey et al., 2014), in the development of business leaders (Baden & Parks, 2013), and broadly in leadership education (Guthrie & Bertrand Jones, 2012). In leadership development organizations, the experiential learning cycle may be used either explicitly or implicitly (Guthrie & Bertrand Jones, 2012; Kolb & Kolb, 2009). Individuals at leadership institutions or programs who are tasked with developing leaders utilize key elements of the cycle (Huey et al., 2014), specifically the reflection and conceptualization phases, to drive home lessons that allow the students to effectively generate and experiment with their own leadership style. Learning about leadership in the classroom, as one example of where development in the cognitive domain can be found, is only one step in the effective leadership learning process.

To impact the affective domain, cognitive learning must be followed up with an experiential process that can leverage the reflection and conceptualization phases of Kolb’s (1984) cycle to alter the behavioral domain (Wallace et al., 2021). These critical elements of this learning process, the reflection and conceptualization phases, can often be overlooked, especially by those that have been in leadership positions for years but lack the leadership education background to understand the process of developing leaders. The importance of reflection in this cycle has been documented (e.g., Healey & Jenkins, 2000; Leberman & Martin, 2004), as well as the importance of reflection in general to leadership development (e.g., Raver Luning & Raver, 2021; Wu & Crocco, 2019). Being a leader does not imply that one can effectively develop leaders or provide leadership development; it requires an educated understanding of the key components of the learning cycle and most importantly, the space in the development process for reflection and conceptualization to occur which helps one in becoming a leader.

Developing Emerging Leaders

Moving beyond the general frameworks that are informing the development of leaders, we must consider the specific methods used for building emerging leaders (Level 1 from Figure 1). In developing leaders, it is important to strike a balance between developing the person through a concentration on the intrapersonal aspects of behavior and teaching the individual how to navigate the social dynamic process (interpersonal aspects) of leadership (Dalakoura, 2010). If too much emphasis is placed on intrapersonal aspects of developing a leader, there is a risk of generating an individual who is highly aware of who he or she is, but lacks the ability to form and foster relationships that are the key to the process of leadership (Wood & Dibben, 2015). On the other hand, if developmental approaches are grounded in merely a process perspective, there is the potential to generate leaders who can form relationships and accomplish shared goals, but lack insight into who they are (Avolio & Gardner, 2005). Before thriving in a leadership role, leaders need to expend effort to develop themselves as individuals first, taking primarily a leader development focus (Wallace et al., 2021). As the individual gains greater self-awareness and strong underlying values, it then becomes important to transition to building skills related to the process components of leadership.

Leader Development

As described in the previous sections, the development of the leader can be maximized by linking cognitive, behavioral, and affective learning to experiential leadership activities that are connected to the four phases of the experiential learning cycle. Allowing space for the reflective and conceptual aspects of learning not only deepens the leader development process but increases the longevity of development for the leader (Guthrie & Bertrand Jones, 2012).

One of the primary goals of integrating these developmental frameworks is to increase self-awareness of basic human functioning and personal values, both of which are central to developing the person as a leader (Karp, 2013; Karp & Helgø, 2009). Capitalizing on this awareness, attention can then begin on specific attributes and skills for personal excellence. One way to approach this development of specific attributes and skills is to categorize them broadly into competencies. Competencies are the clusters of related behaviors (Lombardo & Eichinger, 2009) which stem from the knowledge and skills that drive behavior (Koedijk et al., 2021). Interest in developing competencies has a long history as an approach to leader and leadership development (e.g., Boyatzis, 1982; Lombardo & Eichinger, 2009; McClelland, 1973; Peterson & Seligman, 2004). While there is debate as to the value of competency-based approaches to developing leaders (e.g., Bolden & Gosling, 2006; Conger & Ready, 2004), there has been an ongoing push to integrate some type of competency development as one is growing as a leader (Fowler, 2018; Wallace et al., 2021).

One competency-based approach to leader and leadership development was presented by Macris et al. (in press). This framework breaks down the focus relative to four meta-competencies with several subsidiaries. Two of those meta-competencies and respective subsidiary competencies highlight the intrapersonal aspects of developing as a leader: self-leadership and character. This competency approach provides a way to consider the multiple aspects of leader development and ingrain these competencies using the know, do, be framework linked to the phases of the experiential learning cycle. Mastery of the competencies involves an individual moving along a continuum to develop expertise. The individual initially learns the basics of what the competency is, cognition or knowing. As the individual moves further on the continuum, they begin doing (developing the competency through behaviors), gaining more acumen in the competency. Then, through programs that focus on the experiential learning cycle, specifically the reflective and conceptualization components, the emerging leader gains more expertise in the competency as they begin to value it—be—as part of their leadership identity. Table 1 presents the specific intrapersonal competencies. Ultimately, an approach such as this generates self-aware leaders who have a clear sense of their identity and are invested in their ongoing development.

Leadership Development

Despite the mistaken tendency for many to interchange leader development with leadership development, the two terms signify separate concepts (Day et al., 2014). Leadership development moves beyond just the leader and represents an expansion of collective capability to engage in the social dynamic aspects of leadership, the leadership process (Day, 2000; Wallace et al., 2021). The complex interaction between the leader, the followers, and the teams and organizations in which they are immersed, which is further influenced by the environment, requires a cognitive understanding of the multitude of interacting elements as well as a learned behavioral response. In leadership development, experimentation with group interaction followed by reflective observation and conceptualization is critical to achieve leadership effectiveness (Wallace et al., 2021). The greater the extent this takes place, the greater the organization collectively utilizes the leadership process to effectively achieve its goals and thereby reinforces the leader’s realization of affective learning, in essence emotionally feeling like a leader—being.

Similar to leader development, a competency-based approach can be used for leadership development, which provides a method for those that influence leadership development to have the most impact. Leadership development that incorporates a set of competencies—interpersonal behaviors as well as small unit leadership skills can lead to greater leadership effectiveness (Table 2). Similar to the intrapersonal and character competencies, the leadership competencies incorporate a spectrum of understanding moving from knowledge (cognition) to psychomotor acumen (learning through doing—behaviors) to expertise which centers on affective adoption (being) of the competency. A combination of the leader and leadership competencies provides a robust approach and allows leadership developers a deliberate destination for their development activities.

Developing Leadership Developers

As we consider Level 2 and to a lesser degree Level 3 (a robust discussion of the leadership tutors is beyond the scope of this article and will be addressed in future work) from Figure 1, it is important to consider how to move beyond direct leader and leadership development to developing leadership developers—those directly and indirectly focused on building emerging leaders’ competencies. In many ways, the idea of developing leadership developers can be likened to train-the-trainer concepts. Train-the-trainer models are often used in professional settings as a way to provide training to those responsible for delivering professional development material to a targeted audience (Pancucci, 2007; van Baarle et al., 2017). Yet, there is minimal literature linking train-the-trainer frameworks to leader and leadership development. Persaud et al. (2022) study a link between train-the-trainer programs for opioid reduction in the workplace to leadership program goals; however, this does not link the train-the-trainer model to specific development of leaders or leadership skills. Thus, to gather a robust underpinning for developing leadership developers, we move beyond a focus on train-the-trainer models. One approach to developing leadership developers that extends beyond the train-the-training framework is to create DDOs that focus on an ongoing developmental approach within organizations that are embedded into the culture (Kegan & Lahey, 2016).

Deliberately Developmental Organizations

The central principle with DDO is that organizations are able to thrive when they are aligned with people’s motivations to grow (Kegan et al., 2014a). Developing individuals is woven into the cultural norms of DDOs; they are driven by the notion that adults can grow and everyone within the organization contributes to the growth of one another. There are three main developmental features of DDOs: principles, practices, and community (Kegan et al., 2014b). DDOs are driven by a set of deeply ingrained principles, which drive daily decision making. These principles center on embedding a growth mindset (Dweck, 2016) into the individuals in the organization and weaving a culture of growth mindset (Murphy & Dweck, 2010) into the fabric of the organization.

Developmental practices are applied to carry out these developmental principles in the daily and ongoing operations of DDOs (Kegan et al., 2014b). Developmental practices of DDOs set them apart from other organizations in that they depart from the routines, structure, and language of most organizations. One of the key aspects of developmental practices is that individuals feel they can be their true self in DDOs. They are able to be authentic to their values, which is at the core of developing one’s leader identity (Avolio & Gardner, 2005). Finally, community plays a central role in DDOs where value is placed on the individual, all are held accountable, and there is real and sustained dialogue.

A Framework for Developing Leadership Developers

We propose that to optimize the development of emerging leaders, a concerted effort must be placed on the development of the leadership developers. This can be accomplished through the creation of a DDO concentrated not merely on growth alone but growth within the domains of leadership, specifically ongoing and continual growth of leader and leadership competencies. Considering the three features of a DDO (Kegan et al., 2014b), the developmental principles, practices, and community, within the context of leader and leadership development provide the optimum holistic framework for building a leadership development culture in the organization.

Developmental principles are those that can be understood and embodied by each member of the organization regardless of their job title as it relates to leader and leadership development. They are unifying principles, North Stars, that align the members of the leadership development program or organization so that all are in tune with one another (Kegan & Lahey, 2016). A leadership focused DDO leverages a growth mindset (Dweck, 2016), to not only embrace overcoming obstacles for the emerging leader but also with navigating the complexity of learning successful group interaction. Closely related is that errors and mistakes are allowed and viewed as opportunities for this growth (Kegan et al., 2014b). The experimentation phase of the learning cycle fully expects that mistakes will be made and learned from; this is an essential part of the leader and leadership development process (Wallace et al., 2021). The leadership DDO as an organizational principle provides space for mistakes to happen. More specifically, these mistakes are in the realms of leadership actions and decisions, enabling all those within the program or organization to build and foster their leadership acumen.

There is also interdependence between the desired goals and outcomes of the organization along with the prioritization of the members of the organization (Kegan & Lahey, 2016). This interdependence parallels the ideas of leadership effectiveness providing a balance between results (task and mission accomplishment) and the retention (taking care of the people) of the followers (Horstman, 2016). This interdependence principle suggests that the desired results of the organization can be achieved with a focus on the members. The two elements are not separate or prioritized over one another. Ensuring these principles are realized by all members of the organization is an essential component of a leadership development focused DDO and provides the foundation for its critical practices.

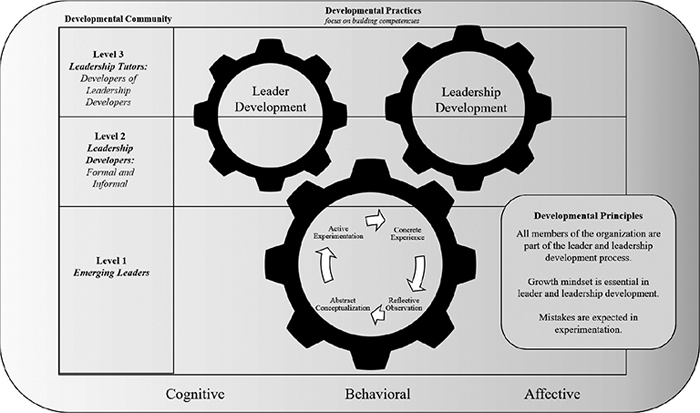

A leadership DDO community comprises all three sub-groups of Figure 1: emerging leaders, formal and informal leadership developers, as well as leadership development tutors charged with developing those that educate others in leadership principles and practices. It is this community that utilizes the experiential learning cycle (Kolb, 1984) to enhance cognitive, behavioral, and affective learning. Both leader and leadership development occur as the developmental practice within the learning cycle. The practices provide output measured with leader and leadership competencies, which are the developmental principles of the DDO.

The developmental practices of a leadership DDO incorporate the elements of the experiential learning cycle along the domains of learning by the developmental community of the program or organization. Whether a formal or informal leadership developer, all members of the leadership DDO play a role in the cognitive, behavioral, and affective learning of the emerging leaders. This is accomplished through understanding the experiential learning cycle as an organizational standard and then actively allowing room for reflective observation, conceptualization, and experimentation to take place. Developmental practices incorporate this cycle in both leader and leadership development, as well as across the three domains of learning as a way to embed the development deeply into the culture of the leadership organization. These practices are specific to leadership DDO’s. Figure 2 presents a framework for how all of these components of a leadership DDO converge.

Figure 2

Leadership Focused Deliberately Developmental Organizational Framework.

Conclusion

Leadership research over the last several decades provided a distinct refutation of the common leadership myths of the past that leadership cannot be taught or that the school of hard-knocks is the only possible avenue for leadership development (e.g., Day et al., 2009; Day & Thornton, 2017; Kolditz et al., 2021; Lunsford & Brown, 2017; Wallace et al., 2021). This article highlights how both leader and leadership development can be embedded into the culture of an organization to foster true development utilizing a DDO (Kegan & Lahey, 2016). This leadership focused DDO is comprised of formal and informal leadership developers, common principles shared across the organization that enhances learning, as well as common practices in which learning is cognitive, behavioral, and affective which serve to generate and inform one’s leader identity. This approach requires a concerted effort from those that develop the developers (leadership tutors) to influence leader and leadership development taking a targeted focus on developing leadership developers, to properly create this framework. More work is certainly needed in studying the effectiveness of such leadership development tutors in creating this framework, the best approaches to developing leadership developers, and the outcomes of developing the emerging leaders.

Acknowledgements

The authors would like to acknowledge the contributions of CAPT Kevin Mullaney, PhD of the Department of Leadership, Ethics, and Law at the United States Naval Academy for his contribution of the leader and leadership competencies presented in Tables 1 and 2.

References

| Anderson, L., & Krathwohl, D. A. (2001). Taxonomy for learning, teaching and assessing: A revision of Bloom’s Taxonomy of Educational Objectives. Longman. |

| Avolio, B. J. (2007). Promoting more integrative strategies for leadership theory-building. American Psychologist, 62(1), 25–33. https://doi.org/10.1037/0003-066X.62.1.25 |

| Avolio, B. J., & Gardner, W. L. (2005). Authentic leadership development: Getting to the root of positive forms of leadership. Leadership Quarterly, 16(3), 315–338. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.leaqua.2005.03.001 |

| Baden, D., & Parkes, C. (2013). Experiential learning: Inspiring the business leaders of tomorrow. Journal of Management Development, 32(3), 295–308. https://doi.org/10.1108/02621711311318283 |

| Bergsteiner, H., & Avery, G. C. (2014). The twin-cycle experiential learning model: Reconceptualising Kolb’s theory. Studies in Continuing Education, 36(3), 257–274. https://doi.org/10.1080/0158037X.2014.904782 |

| Bloom, B. S., Engelhart, M. D., Furst, E. J., Hill, W. H., & Krathwohl, D. R. (1956). Taxonomy of educational objectives: The classification of educational goals. Handbook I: Cognitive domain. David McKay Company. |

| Bolden, R., & Gosling, J. (2006). Leadership competencies: Time to change the tune?. Leadership, 2(2), 147–163. https://doi.org/10.1177/1742715006062932 |

| Boyatzis, R. E. (1982). The competent manager: A model for effective performance. Wiley. |

| Brown, R. P. (2022). Measuring the mist: A practical guide for discovering what really works in leader development. Doerr Institute. |

| Conger, J. A., & Ready, D. A. (2004). Rethinking leadership competencies. Leader to Leader, 2004(32), 41–47. https://doi.org/10.1002/ltl.75 |

| Dalakoura, A. (2010). Differentiating leader and leadership development: A collective framework for leadership development. Journal of Management Development, 29(5), 432–441. https://doi.org/10.1108/02621711011039204 |

| Day, D. V. (2000). Leadership development: A review in context. Leadership Quarterly, 11(4), 581–613. https://doi.org/10.1016/S1048-9843(00)00061-8 |

| Day, D. V., & Dragoni, L. (2015). Leadership development: An outcome-orientated review based on time and levels of analysis. Annual Review of Organizational Psychology and Organizational Behavior, 2, 133–156. https://doi.org/10.1146/annurev-orgpsych-032414-111328 |

| Day, D. V., Fleenor, J. W., Atwater, L. E., Sturm, R. E., & McKee, R. A. (2014). Advanced in leader and leadership development: A review of 25 years of research and theory. Leadership Quarterly, 25(1), 63–82. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.leaqua.2013.11.004 |

| Day, D. V., Harrison, M. M., & Halpin, S. M. (2009). An integrative approach to leader development: Connecting adult development, identity, and expertise. Psychology Press. |

| Day, D. V., & Thornton, A. M. A. (2017). Leadership development. In J. Antonakis & D. V. Day (Eds.), The nature of leadership (pp. 354–381). SAGE Publications. |

| Day, D. V., & Zaccaro, S. J. (2004). Toward a science of leader development. In D. V. Day, S. Zaccaro, & S. M. Halgin (Eds.), Leader development for transforming organizations (pp. 403–420). Psychology Press. |

| Dweck, C. S. (2016). Mindset: The new psychology of success. Ballantine Books. |

| Fowler, S. (2018). Toward a new curriculum of leadership competencies: Advances in motivation science call for rethinking leadership development. Advances in Developing Human Resources, 20(2), 182–196. https://doi.org/10.1177/1523422318756644 |

| Guthrie, K. L., & Bertrand Jones, T. (2012). Teaching and learning: Using experiential learning and reflection for leadership education. New Directions for Student Services, 2012(140), 53–63. https://doi.org/10.1002/ss.20031 |

| Harrow, A. J. (1972). A taxonomy of the psychomotor domain. David McKay Co. |

| Healey, M., & Jenkins, A. (2000). Kolb’s experiential learning theory and its application in geography in higher education. Journal of Geography, 99(5), 185–195. https://doi.org/10.1080/00221340008978967 |

| Hollander, E. P. (2009). Inclusive leadership: The essential leader-follower relationship. Routledge. |

| Hoque, M. E. (2016). Three domains of learning: Cognitive, affective and psychomotor. The Journal of EFL Education and Research, 2(2), 45–52. |

| Horstman, M. (2016). The effective manager. Wiley. |

| Huey, W. S., Smith, D. G., Thomas, J. T., & Carlson, C. R. (2014). The great outdoors: Comparing leader development programs at the U.S. Naval Academy. Journal of Experiential Education, 37(4), 367–381. https://doi.org/10.1177/1053825914547625 |

| Karp, T. (2013). Developing oneself as a leader. Journal of Management Development, 32(1), 127–140. https://doi.org/10.1108/02621711311287080 |

| Karp, T., & Helgø, T. I. (2009). Leadership as identity construction: The act of leading people in organizations: A perspective from the complexity sciences. Journal of Management Development, 28(10), 880–896. https://doi.org/10.1108/02621710911000659 |

| Kegan, R., & Lahey, L. L. (2016). An everyone culture: Becoming a deliberately developmental organization. Harvard Business Review Press. |

| Kegan, R., Lahey, L., Fleming, A., & Miller, M. (2014a). Making business personal. Harvard Business Review. |

| Kegan, R., Lahey, L., Fleming, A., Miller, M., & Markus, I. (2014b). The deliberately developmental organization (pp. 1–14). Way to Grow. |

| Koedijk, M., Renden, P. G., Oudejans, R. R., Kleygrewe, L., & Hutter, R. V. (2021). Observational behavior assessment for psychological competencies in police officers: A proposed methodology for instrument development. Frontiers in Psychology, 12, 589258. https://doi.org/10.3389/fpsyg.2021.589258 |

| Kolb, A. Y., & Kolb, D. A. (2009). Experiential learning theory: A dynamic, holistic approach to management learning, education and development. In S. J. Armstrong, & C. V. Fukami (Eds.), The sage handbook of management learning, education and development (pp. 42–68). SAGE Publications Ltd. https://doi.org/10.4135/9780857021038.n3 |

| Kolb, D. A. (1984). Experiential learning: Experience as the source of learning and development (Vol. 1). Prentice-Hall. |

| Kolb, D. A., Boyatzis, R. E., & Mainemelis, C. (2014). Experiential learning theory: Previous research and new directions. In R. J. Sternberg & L. Zhang (Eds.), Perspectives on thinking, learning, and cognitive styles (pp. 227–248). Routledge. |

| Kolditz, T., Gill, L, & Brown, R. P. (2021). Leadership reckoning: Can higher education develop the leaders we need? Monocle Press. |

| Krathwohl, D. R., Bloom, B. S., & Masia, B. B. (1964). Taxonomy of educational objectives: Handbook II: Affective domain. David McKay Co. |

| Leberman, S. I., & Martin, A. J. (2004). Enhancing transfer of learning through post-course reflection. Journal of Adventure Education & Outdoor Learning, 4(2), 173–184. https://doi.org/10.1080/14729670485200521 |

| Lombardo, M. M., & Eichinger, R. W. (2009). FYI: For your improvement: A guide for development and coaching. Lominger International. |

| Lunsford, L. G., & Brown, B. A. (2017). Preparing leaders while neglecting leadership: An analysis of U.S. collegiate leadership centers. Journal of Leadership & Organizational Studies, 24(2), 261–277. https://doi.org/10.1177/1548051816662613 |

| Macris, J., Thomas, J., Ledford, A., Mullaney, K., & Raver, C. K. (in press). Leadership and character development at the U.S. Naval Academy. In M. Matthews & R. Lerner (Eds.), Handbook of character development, volume 2. Routledge. |

| McClelland, D. (1973). Testing for competence rather than intelligence. American Psychologist, 28(1), 1–14. https://doi.org/10.1037/h0034092 |

| Murphy, M. C., & Dweck, C. S. (2010). A culture of genius: How an organization’s lay theory shapes people’s cognition, affect, and behavior. Personality and Social Psychology Bulletin, 36(3), 283–296. https://doi.org/10.1177/0146167209347380 |

| Pancucci, S. (2007). Train the trainer: The bricks in the learning community scaffold of professional development. International Journal of Educational and Pedagogical Sciences, 1(11), 597–604. https://doi.org/10.5281/zenodo.1076078 |

| Persaud, E., Weinstock, D., & Landsbergis, P. (2022). Opioids and the workplace prevention and response train-the-trainer and leadership training mixed methods follow-up evaluation. Annals of Work Exposures and Health, 66(5), 591–601. https://doi.org/10.1093/annweh/wxab112 |

| Peterson, C., & Seligman, M. (2004). Character strengths and virtues: A handbook and classification. Oxford University Press. |

| Pierre, E., & Oughton, J. (2007). The affective domain: Undiscovered country. College Quarterly, 10(4), 1–7. |

| Raver Luning, C., & Raver, S. (2021). Transitions and identity: The courage to identify as a woman in leadership. In J. Moss-Breen, M. van der Steege, S. Martin, & J. Glick (Eds.), Women courageous: Leading through the labyrinth (pp. 299–317). Emerald Publications. |

| Silva, A. (2016). What is leadership? Journal of Business Studies Quarterly, 8(1), 1–5. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.pedn.2006.10.002 |

| Simm, D., & Marvell, A. (2015). Gaining a “sense of place”: Students’ affective experiences of place leading to transformative learning on international fieldwork. Journal of Geography in Higher Education, 39(4), 595–616. https://doi.org/10.1080/03098265.2015.1084608 |

| van Baarle, E. Hartman, L., Verweij, D., Molewijk, B., & Widdershoven, G. (2017). What sticks? The evaluation of a train-the-trainer course in military ethics and its perceived outcomes. Journal of Military Ethics, 16(1–2), 56–77. https://doi.org/10.1080/15027570.2017.1355182 |

| Wallace, D. M., Torres, E. M, & Zaccaro, S. J. (2021). Just what do we think we are doing? Learning outcomes of leader and leadership development. Leadership Quarterly, 32(5), 101494. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.leaqua.2020.101494 |

| Wood, M., & Dibben, M. (2015). Leadership as relational process. Process Studies, 44(1), 24–47. https://doi.org/10.2307/44798050 |

| Wu, Y., & Crocco, O. (2019). Critical reflection in leadership development. Industrial and Commercial Training, 51(7/8), 409–420. https://doi.org/10.1108/ICT-03-2019-0022 |