FEATURE ARTICLE

We Don’t Do that Here: Using Role Playing and Character Battle Drills to Develop Upstander Behavior at West Point

Everett S. Spain, United States Military Academy

Yasmine L. Konheim-Kalkstein, United States Military Academy

Ryan G. Erbe, United States Military Academy

Corrine N. Wilsey, United States Military Academy

Stacey F. Rosenberg, United States Military Academy

ABSTRACT

Background: The Army is focused on the prevention of harmful interpersonal behaviors such as sexual harassment and sexual assault. Training soldiers who may witness these behaviors to intervene is considered paramount to the Army’s prevention efforts. Objective: To increase the propensity and efficacy of cadets (undergraduate college students) employing upstander behaviors when witnessing harmful interpersonal behaviors in less governed spaces, the United States Military Academy at West Point facilitated two scenario-based role-playing workshops to develop its cadets while piloting new methods of training intervention behaviors. Methods: Both workshops had cadets improvise roles as upstanders, perpetrators, victims, and witnesses. The first workshop focused on developing cadets’ propensity (courage) to intervene and intentionally provided cadets with little guidance on if and how they should intervene, allowing them to develop their own workable intervention strategies and skills. The second workshop focused on developing cadets’ effectiveness during an intervention by having them apply the new Character Battle Drill (CBD) concept, which is a specific sequence of action steps to follow, including specific scripts to say during an intervention. Results: In both workshops, cadets reported higher levels of engagement than traditional forms of bystander training. Conclusions: Improvisational role playing seems promising for future training. Lessons-learned, limitations, and areas of future research are discussed.

Keywords: Harmful Interpersonal Behaviors, Bystander, Upstander, Intervention, Courage

Citation: Journal of Character & Leadership Development 2023, 10: 263 - http://dx.doi.org/10.58315/jcld.v10.263

Copyright: © 2023 The author(s).

This is an Open Access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/), which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original work is properly cited.

CONTACT Yasmine Kalkstein yasmine.kalkstein@westpoint.edu

Published: 09 June 2023

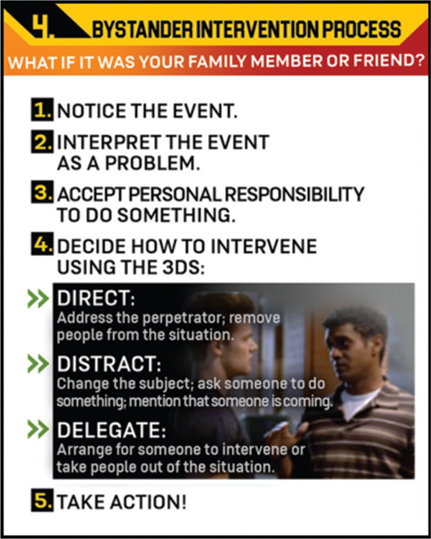

Harmful interpersonal behaviors (such as sexual misconduct, racism, ostracism, and bullying) often occur in the presence of individuals, who, when helpful (such as intervening and interrupting), reduce the prevalence of these behaviors (Hamby et al., 2016). The Army, therefore, considers training individuals to act as upstanders, bystanders who choose to intervene despite risk (Devine & Cohen, 2007; Dunn, 2009), to be an important element in prevention. To this end, the Army widely disseminates the Bystander Intervention Process (Figure 1) to its personnel during annually mandated Sexual Harassment/Assault, Response and Prevention (SHARP) training.

Figure 1

U.S. Army Bystander Intervention Process (U.S. Army, 2021)

Though research has established that helpful bystanders lead to more positive victim outcomes, many bystanders still hesitate to intervene on behalf of the victim (Devine & Cohen, 2007). While most adults are good at recognizing inappropriate behavior, lower levels of moral ownership (Butler et al., 2021), moral efficacy (Mostafa, 2019), and moral courage reduce the likelihood of intervening (Blasi, 1980). In addition, the stress of being in a dangerous situation can lead to an inability to think or act (Abrams et al., 2009). From a simple utilitarian perspective, when potential upstanders perceive that the benefits of intervening do not outweigh the personal and professional risks of doing so, they are incentivized to mind their own business (Nicholson & Snyder, 2012).

Yet, behavioral economics and psychology argue that people do not always act rationally, so having bystanders practice intervention behaviors makes it more likely they will do so through the building of habit (Devine & Cohen, 2007; Etzioni, 1987). Additionally, confidence to intervene is facilitated by being taught the necessary intervention skills (Vera et al., 2019). Specifically in the realm of sexual violence, prosocial behavioral practices must be taught to counter social norms and behaviors that perpetuate sexual violence (Christensen, 2013; Kettrey et al., 2019).

The Army has generally approached the delivery of upstander intervention through large-group, slideshow-assisted briefings. Tens of thousands of supervisors are required to delivery SHARP training annually. Although they are encouraged to incorporate discussions and intervention scenarios, many, likely only conduct the minimum requirement based on other training requirements and commitments. The recommendation has been made to move away from standardized large group training toward smaller-group, scenario-based training, which has, in at least one unit, resulted in greater engagement (Urben, 2014). Similarly, a meta-analysis of college-level sexual assault prevention training indicated that lectures may be ineffective at changing attitudes toward sexual assault (Vladutiu et al., 2011).

One of the most engaging and promising pedagogies to teach skills is role playing (Manzoor et al., 2012; Sogunro, 2004, Stevens, 2015). Studies show that across educational settings, including medicine, business (Barrera et al., 2021), and foreign language learning (Burenkova et al., 2015), role playing leads to greater engagement and better academic performance (Barrera et al., 2021). Perhaps because of the greater engagement, role playing can lead to deeper processing of material, resulting in improved knowledge of the subject (Manzoor et al., 2012). Notably, role playing can increase empathy by promoting perspective taking (Corredor et al., 2021; Larti et al., 2018). More recent works have similarly cited role-playing as especially effective in training leadership behaviors in stressful situations such as crisis and hostage negotiations (van Hasselt et al., 2008) and in the training of peer providers (Oh & Solomon, 2014).

Improvisational role-playing allows participants to experience an everyday scenario with reduced social risk. Schwenke et al. (2021) found that improvisational role-play increased participants’ creativity, mindfulness, tolerance of uncertainty, self-esteem, self-efficacy, and resilience significantly when compared to the control group that did not participate in training.

The prevention of harmful interpersonal behaviors is of concern to West Point, and upstanders are vital in the prevention process. Training can increase efficacy and propensity to intervene; however, traditional SHARP training may not be considered engaging (Urben, 2014), and standardized materials do not build in practicing intervention skills. Given the reported benefits of role-playing (Sogunro, 2004) on learning interpersonal skills, in early 2022, leaders at West Point facilitated two different scenario-based role-playing workshops to develop its cadets while piloting new methods of training intervention behaviors. In Workshop 1, cadets both role-played and watched their peers role play through improvised responses to different scenarios where an upstander could likely mitigate or deter harmful interpersonal behaviors. Following the experiential, improvisational role plays, the entire group was led through a facilitated reflection process. Workshop 2 used a substantially smaller sample to conduct a proof of concept (pilot) focused on developing cadets’ intervention skills to be used after deciding to intervene by providing a Character Battle Drill (CBD) of specific set of actions to take and scripts to say during cadets’ practice of being an upstander. Additionally, Workshop 2 piloted training in a realistic environment with immediate feedback.

Workshop 1- Peer-led Bystander Intervention Role Playing and Guided Reflection

Method

Role Plays

On April 7, 2022, United States Military Academy (USMA) held a 3-h role-playing intervention workshop for all 4,400 cadets. The Corps were divided into mixed gender and class groups within their normal company (there are 36 companies with ~120 cadets per company) of approximately 30 cadets. Each small group was led by both a cadet facilitator running the bystander intervention role-play scenario activity and a trained staff/faculty mentor to ensure completion of the scenarios and subsequent guided reflection.

Materials

Role Plays

Over the course of the 2021–2022 academic year, USMA SHARP professionals worked with the cadets of the West Point Theater Arts Guild to develop several cadet-specific, situational role-play scenarios (Table 1) used in both workshops. For each scenario, facilitators received a scenario description, participant role cards for individual roles with starter prompts to support participation, an end-state (describing for the facilitator what action[s] needed to be achieved to conclude the role-play), and scenario-based debriefing questions for both witnesses and participants to process their experiences.

Survey

Following the workshop, cadets were asked to complete an anonymous feedback survey via a facilitator-provided QR-code driven questionnaire. At that time point, participants reported their engagement during the workshop, their perceived competency before they started the workshop and after the workshop in preventing and responding to sexual violence, and actions they would likely take after the workshop (Tables 2–4).

Procedure

Training the Facilitators

The SHARP professionals recruited and trained 144 cadets and 144 staff/faculty to prepare them for the workshop. During the 1.5-h training of trainers for cadets, cadet leaders were presented a video showcasing what the role-plays should look like in terms of structure, followed by time to practice the activity among themselves and ask questions of the subject matter experts. During the staff/faculty version, instruction focused on facilitating the after-workshop reflection. In both sessions, facilitators were provided with their left and right boundaries and encouraged to work with their counterpart to ensure everyone was prepared for their role.

Day of Workshop

The first 2-h of the 3-h training were dedicated to scenario role-plays facilitated by peer-facilitators. This was followed by a 1-h long reflection session facilitated by staff/faculty mentors. To begin, peer-facilitators within each group randomly distributed the roles of the various scenarios to the group participants. Most cadets were able to actively participate in at least one of the role-play scenarios throughout the 2-h dedicated to role-playing. About one in four cadets got to experience playing an upstander role in one of the scenarios, while other cadets were assigned roles as perpetrators, conformists, and colluders.

To support reflection and synthesize the lessons learned, the staff/faculty facilitator led a guided reflection discussion after the role play scenarios were complete. Following the discussion, cadets were asked to complete the feedback survey. Six months later, the authors formally requested and received approval for use of this de-identified archival data detailed in the results section.

Results

Of the approximate 4,400 cadets who participated in the training, 710 cadets completed the optional post-activity survey, which represents approximately 17% of cadets who participated in the activity. The only demographic data collected were their company and class. Of the respondents, 201 were freshmen, 194 were sophomores, 146 were juniors, and 166 were seniors, and the respondents were distributed nearly equally across regiments (i.e., groups of nine companies).

Most respondents (91%) self-reported that they were actively engaged in the activity, with 56% of respondents indicating they were actively engaged through the entire activity (Table 2). Respondents were also offered the option of adding additional comments as free responses at the end of the survey. In that section, several cadets highlighted that the training was more engaging and beneficial than traditional training, largely due to role playing.

Results (Table 3) suggest improved perceived confidence in managing sexual violence after having participated in the workshop (χ2[3] = 30.08, p < 0.00001). At the end of the workshop, almost 12% more indicated that “I know what to do and feel ready to do it.” Also, cadets were asked how prepared they felt to respond to sexual violence before the activity, and how prepared they feel now. After the activity, 13.7% more cadets indicated “I know what to do and feel ready to do it” (not shown in table).

Additionally, most cadets indicated they would take action because of the training (Table 4). Of those who indicated that they would take action after the training, nearly 21% of respondents indicated that they thought they would participate in all eight of the provided action items. On average, respondents selected 4.7 action items.

| What actions do you think you will take after today’s activity (n = 632)* | |

| - Work to build trust and a positive culture of support | 462 (73.1%) |

| - Be more aware of signs of sexual assault/harassment | 435 (68.8%) |

| - Be a better leader | 427 (67.6%) |

| - Live more fully the Army values | 380 (60.1%) |

| - Help others be more accountable for their actions | 377 (59.7%) |

| - Be more accountable for my own actions | 371 (58.7%) |

| - Take more time for personal reflection | 359 (56.8%) |

| - Share this information with others | 245 (38.7%) |

| - I will not take actions because of today’s activity | 32 (5.1%) |

| - I don’t know | 29 (4.6%) |

| - Other | 12 (1.9%) |

| *Participants could indicate more than one action | |

Additionally, participants were offered the opportunity to share about the personal and professional impact of this training via an open response. Of the 710 respondents, 51% (n = 397) completed this question. Of those who responded to this question, 12.6% (n = 50) indicated that they did not think the activity would have an impact, and 1% (n = 4) stated that they believed the training negatively impacted those who had experienced prior violence and/or harassment. The other 85% of open responses grouped into the following positive themes: Increased awareness, tools to deal with their own experiences, opportunity for self-reflection, increased confidence in standing up to bad behavior and difficult situations, boosted team cohesion, and reinforced moral courage and positive values.

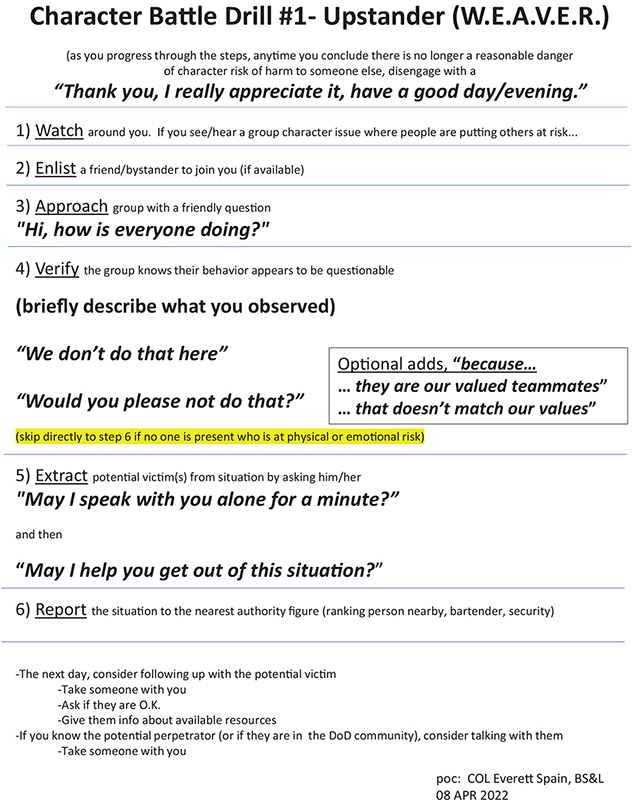

Workshop 2- Character Battle Drills

The results from Workshop 1 suggest that the bystander intervention role-playing was more engaging, and possibly more influential, than other types of training cadets that had previously received at West Point. Workshop 2 also used role playing but piloted a CBD to provide scaffolding of intervention skills. The CBD was inspired by integrating the Army’s Bystander Intervention Process (Figure 1) with the military’s concept of combat battle drills. Combat battle drills are a short series of specific action steps soldiers should take immediately when in a dangerous and urgent situation, such as when receiving incoming artillery fire or treating a fellow soldier’s serious combat wound, to increase the likelihood of survival or victory. Combat battle drills are trained through repetition, so that soldiers do not have to pause to make decisions when faced with mortal danger, and time is a critical factor. The CBD provided aspiring upstanders with a specific set of actions to take and scripts to say during interventions in dangerous social situations where others are at risk. The intention was to run a workshop to examine whether a CBD would increase upstander self-efficacy for interventions.

Method

Participants

The participants for this workshop were the cadet freshmen enrolled in one section of USMA’s Character Growth Seminar (a pilot course that met once per week for 75-min across two academic semesters). On the day of the workshop, class attendance was 14 male cadets and two female cadets (n = 16; note that year, 24.8% of the freshmen were female). Seven months later, with the intent of research, the participants were asked to consider answering a brief online questionnaire about their experience. Ten provided consent and participated.

Materials

Character Battle Drill

During the year prior to the CBD workshop, the authors developed and shared a draft CBD with a section of 14 mostly sophomore West Point cadets and with approximately 35 West Point faculty members, both in colloquium-style discussions, requesting feedback on the concept and updating it appropriately. The CBD subsequently used in Workshop 2 was a six-step process (Figure 2), organized via the pneumonic acronym W.E.A.V.E.R.

Figure 2

Character Battle Drill (W.E.A.V.E.R.) for Upstander Training Used in Workshop 2

Procedure

To create as realistic an environment as possible to apply the CBD, the class took place at the First Class (or “Firstie”) Club, a bar and grill restaurant on the West Point campus created primarily for the use of cadet seniors and their guests during their off-duty hours. The 65-min event included (1) 15 min of orientation to the CBD, (2) three 10-min role-playing scenarios (Table 1) followed by a 2-min on-location after action review, and (3) a 10-min overall after-action review (AAR). Cadet played a different role in each of the three scenarios; all took a turn as an upstander, and played either the victim, bystander, or perpetrator for the other two scenarios.

At the beginning of each scenario, faculty facilitators placed an aspiring upstander team of two cadets at a table near the victim and perpetrators. The victims and perpetrators received a set of written instructions on their role. The aspiring upstander team received no role-playing instructions in addition to the hardcopy CBD, which they were encouraged to refer to during the scenarios. Role-plays begin with victims and perpetrators acting while the aspiring upstander team was instructed to observe and intervene at the right time.

After each role play, faculty held a debrief with the participants. After the three rotations (nine separate events) were completed, a large group AAR was held, in which cadets provided feedback on the role-playing scenarios they experienced, including comments about the helpfulness of the CBD. Within three days following the event, feedback was sought from the six faculty facilitators to assess engagement, confidence in ability to intervene, and which factors were particularly impactful.

Initial observations from faculty suggested that cadets found the experience to be engaging due to the challenge and authenticity. Faculty also felt that the debrief after each role play was particularly useful for developing perspective taking and allowed for reflective learning. The AAR with cadets confirmed that practicing being an upstander was critical to their learning, and that the context of the Firstie Club made the experience more realistic. Cadets indicated they found the script to be a helpful point from which to launch, but some also indicated that they sometimes have their own style or words that work better for them.

Results

Eight of the 10 participants who completed the post-workshop survey endorsed the experience as very or extremely engaging, and three of 10 cadets indicated they were more confident to act as an upstander because of the training (Table 5). Three of 10 cadets had been in a situation since the workshop where they noticed someone taking advantage of someone else. All three of these cadets indicated that they used skills practiced during the workshop; all indicated they used the “enlist a friend of bystander to go with you.” Seven of 10 cadets indicated that the W.E.A.V.E.R. framework was either “extremely useful” or “very useful” for navigating challenging intervention situations in real life, and seven of 10 cadets indicated that hosting the workshop in the Firstie Club was “very worthwhile” or “extremely worthwhile” for learning how to better intervene in real life.

Discussion

Workshop 1 was designed primarily to develop cadets’ efficacy in making the decision to intervene, while Workshop 2 was designed primarily to develop participants’ social skill in navigating an intervention to a positive outcome. Cadets who went through Workshop 1 found it to be engaging and felt more prepared on the whole to deal with sexual violence after the upstander training. Cadets who went through the CBD workshop (Workshop 2) found it engaging; most found the CBD, which includes both steps and specific scripts to say, to be very useful. This was particularly exemplified by the three cadets who experienced an opportunity to be an upstander in real life after the workshop; all reported using skills they learned in the training in the actual situation they encountered.

Facilitating both workshops highlighted several key learnings. First, both workshops suggest that regarding upstander training, role playing is an engaging way to teach intervention skills. Both workshops required the participants to play roles in the scenario beyond just the upstander, including perpetrators, victims, and witnesses. This may have allowed for the participants to gain further insight into the motivations of other actors in similar scenarios, potentially becoming more effective as a future bystander. Notably, many reported that playing the role of the potential perpetrator was the most challenging. Third, both workshops highlighted a variety of harmful interpersonal behaviors, instead of focusing solely on one type of harmful behavior, as is often traditional for Army training. By expanding the type of harmful interpersonal behaviors that the training focused on, the authors hope that the participants were able to gain a general competency at upstander behavior that can be applied to various types of harmful behaviors during their lifetimes, and not limited to upstanding in just one domain. Fourth, coupling feedback and reflection is important to role-playing when the primary objective is skill development. Guiding the participants through post-workshop, deliberate reflection suggests it crystallizes the lessons learned (Miller & Brabson, 2021). This enables participants to deeply learn from their training experiences.

Limitations and Future Research

Both studies had limitations. First, neither workshops established cadets’ baseline efficacy of their propensity to intervene. Second, no process logs were completed to ensure fidelity across the different simultaneous groups (Workshop 1 had over 144 different 30-cadet groups, and Workshop 2 had three different five to six person groups).

Additionally, Workshop 2’s questionnaire was issued seven months after the training event, the sample size was small, and the participants were also involved in the previous workshop the day before, so it is hard to separate the effects of the two events in Workshop 2’s outcomes.

Given a response rate of approximately 20% in Workshop 1’s survey and 62% in Workshop 2’s survey, selection bias may limit the validity of the results. For both studies, generalizability to a civilian college-student population and civilian adult population is unknown, as cadets at USMA are in an environment where there is a saturation of espoused pro-bystander slogans such as “do the right thing,” “see something, say something,” and “live above the common level of life.” Finally, both workshops are resource intensive, particularly for facilitator/evaluator availability and training, though this is significantly reduced by having participants play all the roles and can be further reduced by having participants serve as evaluators, which, the authors predict, would also facilitate learning.

Encouragingly, both workshops generated many questions for future research about improvisation and CBD training. One is the intersection of bystanders’ social skill and the optimal use of organizationally espoused intent, steps, and scripts. Regarding the CBD concept, there was some debate in the development of the tool, to what extent the CBD should or should not include specific scripts, such as the W.E.A.V.E.R.’s “We don’t do that here.” For example, one group who presented with high-social skill successfully worked as team to distract the perpetrators via engaging conversation, so they could simultaneously remove the victim from the scenario, but they did not use the CBD’s specific scripts. It is possible that cadets who presented with lower self-efficacy around this kind of social situation tended to lean more on the steps and specific scripts during the scenarios as an upstander.

More research is needed on how behaviors learned in the context of a workshop translate to them being used outside of the workshop. While our research suggests engagement while learning and perceived self-efficacy was higher as a result of this type of training, we do not know enough about how the skills are translated and utilized in real-life situations. Additional areas for future study include researching potential differences in upstander behaviors by gender and ethnicity, and other demographics.

Certainly, the CBD’s steps and scripts should be studied for efficacy and optimized, if found effective. When studying bullying in schools, scholars have found upstander scripts are more effective when students and administration write them together (Devine & Cohen, 2007). Therefore, if used, every organization may be wise to write their own in a collaborative process, thus facilitating buy-in and customization. Finally, participants (cadets) recommended creating a version of the CBD designed specifically for use in online situations, as significant amounts of harmful interpersonal behaviors happen in the cyber domain.

Conclusion

Knowing that bystanders who observe corrosive behavior are likely to recognize the need for intervention but not likely to intervene, the experiences with two workshops at West Point show that organizations may be able to positively influence their peoples’ upstander behavior through role-play training. Though follow-on research is needed on the topic, organizations who facilitate organizational-level role-playing of upstander behavior, formally create an adaptive rubric for aspiring upstanders (such as a CBD), and facilitate feedback from observers and self-reflection of participants, may build their members’ propensity to intervene and efficacy during their intervention, creating a safer and more effective environment for all.

Author Note

The views expressed herein are those of the authors and do not represent the U.S. Military Academy, the Department of the Army, or the Department of Defense. We have no known conflict of interest to disclose.

References

| Abrams, M. P., Nicholas Carleton, R., Taylor, S., & Asmundson, G. J. (2009). Human tonic immobility: Measurement and correlates. Depression and Anxiety, 26(6), 550–556. https://doi.org/10.1002/da.20462 |

| Dellinger Barrera, F., Venegas-Muggli, J. I., & Nuñez, O. (2021). The impact of role-playing simulation activities on higher education students’ academic results. Innovations in Education and Teaching International, 58(3), 305–315. https://doi.org/10.1080/14703297.2020.1740101 |

| Blasi, A. (1980). Bridging moral cognition and moral action: A critical review of the literature. Psychological Bulletin, 88, 1–45. https://doi.org/10.1037/0033-2909.88.1.1 |

| Burenkova, O. M., Arkhipova, I. V., Semenov, S. A., & Samarenkina, S. Z. (2015). Motivation within role-playing as a means to intensify college students’ educational Activity. International Education Studies, 8(6), 211–216. https://doi.org/10.5539/ies.v8n6p211 |

| Butler, L. C., Graham, A., Fisher, B. S., Henson, B., & Reyns, B. W. (2021). Examining the effect of perceived responsibility on online bystander intervention, target hardening, and inaction. Journal of Interpersonal Violence, 37(21–22), NP20847–NP20872. https://doi.org/10.1177/08862605211055088 |

| Christensen, M. C. (2013). Using theater of the oppressed to prevent sexual violence on college campuses. Trauma, Violence, & Abuse, 14(4), 282–294. https://doi.org/10.1177/1524838013495983 |

| Corredor, J., Castro-Morales, C., & Jiménez-Rozo, T. A. (2021). Chapter 15: Document-based historical role-playing as a tool to promote empathy and structural understanding in historical memory education. In W. López López, & L. K. Taylor (Eds.), Transitioning to peace (pp. 269–285). Psychology Book Series, Springer. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-030-77688-6_15 |

| Devine, J., & Cohen, J. (2007). Making your school safe: Strategies to protect children and promote learning. Teachers College Press. |

| Dunn, S. T. M. (2009). Upstanders: Student experiences of intervening to stop bullying (Doctoral dissertation, University of Alberta). https://central.bac-lac.gc.ca/.item?id=NR55337&op=pdf&app=Library&oclc_number=741397716 |

| Etzioni, A. (1987). How rational we? Sociological Forum, 2(1), 1–20. https://doi.org/10.1007/BF01107891 |

| Hamby, S., Weber, M. C., Grych, J., & Banyard, V. (2016). What difference do bystanders make? The association of bystander involvement with victim outcomes in a community sample. Psychology of Violence, 6(1), 91–102. https://doi.org/10.1037/a0039073 |

| Kettrey, H. H., Marx, R. A., Tanner-Smith, E. E., Kettrey, H. H., & Hall, B. (2019). Effects of bystander programs on the prevention of sexual assault among. Campbell Systematic Reviews, 15(1–156). https://doi.org/10.4073/csr.2019.1 |

| Larti, N., Ashouri, E., & Aarabi, A. (2018). The effects of an empathy role-playing program for operating room nursing students in Iran. Journal of Educational Evaluation for Health Professions, 15. https://doi.org/10.3352/jeehp.2018.15.29 |

| Manzoor, I., Mukhtar, F., & Hashmi, N. R. (2012). Medical students’ perspective about role-plays as a teaching strategy in community medicine. Journal of the College of Physicians and Surgeons Pakistan, 22(4), 222–225. |

| Miller, T., & Brabson, J. T. T. (2021). Metacognitive reflection. Military Learning, 61–77. |

| Mostafa, A. M. S. (2019). Abusive supervision and moral courage: Does moral efficacy matter? PSU Research Review, 3(2), 145–155. https://doi.org/10.1108/PRR-08-2018-0024 |

| Nicholson, W., & Snyder, C. M. (2012). Microeconomic theory: Basic principles and extensions. Cengage Learning. |

| Oh, H., & Solomon, P. (2014). Role-playing as a tool for hiring, training, and supervising peer providers. The Journal of Behavioral Health Services & Research, 41(2), 216–229. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11414-013-9350-2 |

| Schwenke, D., Dshemuchadse, M., Rasehorn, L., Klarhölter, D., & Scherbaum, S. (2021) Improv to improve: The impact of improvisational theater on creativity, acceptance, and psychological well-being. Journal of Creativity in Mental Health, 16, 31–48. https://doi.org/10.1080/15401383.2020.1754987 |

| Sogunro, O. A. (2004). Efficacy of role-playing pedagogy in training leaders: Some reflections. Journal of Management Development, 23(4), 355–371. https://doi.org/10.1108/02621710410529802 |

| Stevens, R. (2015). Role-play and student engagement: Reflections from the classroom. Teaching in Higher Education, 20(5), 481–492. https://doi.org/10.1080/13562517.2015.1020778 |

| Urben, H. (2014). Extending SHARP best practices. Military Review, 29–32. https://www.armyupress.army.mil/Portals/7/military-review/Archives/English/MilitaryReview_20140430_art008.pdf |

| Van Hasselt, V. B., Romano, S. J., & Vecchi, G. M. (2008). Role playing: Applications in hostage and crisis negotiation skills training. Behavior Modification, 32(2), 248–263. https://doi.org/10.1177/0145445507308281 |

| Vera, E., Hill, L., Daskalova, P., Chander, N., Galvin, S., Boots, T., & Polanin, M. (2019). Promoting upstanding behavior in youth: A proposed model. The Journal of Early Adolescence, 39(7), 1020–1049. https://doi.org/10.1177/0272431618798514 |

| Vladutiu, C. J., Martin, S. L., & Macy, R. J. (2011). College-or university-based sexual assault prevention programs: A review of program outcomes, characteristics, and recommendations. Trauma, Violence, & Abuse, 12(2), 67–86. https://doi.org/10.1177/1524838010390708 |