FEATURE ARTICLE

Creating a Culture of Character Growth: Developing Faculty Character and Competence at the United States Military Academy

Ryan G. Erbe, United States Military Academy

Darcy Schnack, United States Military Academy

Peter Meindl, United States Military Academy

ABSTRACT

Background: Institutions of higher education, specifically service academies, interested in developing character in their students/cadets should consider creating a culture of character growth to accomplish their task. One potential way to do this is to focus on developing faculty character along with character competence as it relates to student/cadet character formation.

Objective: At the United States Military Academy, we recently piloted a character faculty development series for Center for Enhanced Performance faculty aimed at improving faculty character formation, increasing faculty competence with respect to developing cadet character through one-on-one relationships, and integrating character formation into their teaching. The goal of this project was to assess feasibility and acceptability of the series.

Methods: The Center for Enhanced Performance faculty experienced a three-part character faculty development series: (1) Faculty character formation, (2) Developing cadet character through one-on-one relationships, and (3) Integrating character into the classroom. To assess feasibility and acceptability of the series, a survey was sent to faculty after completion.

Results: A total of nine faculty members completed the survey and found the training worthwhile, that it increased their confidence in developing cadets’ character and integrating character formation into their teaching, along with each character formation tool being useful.

Conclusions: Character faculty developing series should be tried and can be feasible and acceptable to faculty.

Keywords: Character, Virtue Formation, Faculty Development, Higher Education

Citation: Journal of Character & Leadership Development 2023, 10: 275 - http://dx.doi.org/10.58315/jcld.v10.275

Copyright: © 2023 The author(s). This is an Open Access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/), which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original work is properly cited.

CONTACT Ryan G. Erbe ryan.erbe@westpoint.edu

Published: 25 October 2023

Introduction

At the heart of the United States Military Academy (USMA) mission is to “educate, train, and inspire the Corps of Cadets so that each graduate is a commissioned leader of character” (United States Military Academy, n.d.). Toward that end, in 2020, the Superintendent proposed various Lines of Effort (LOE) described in “The USMA Strategy.” The second line of effort, also known as LOE 2, is to “Create a Culture of Character Growth.” Specifically, LOE 2 states, “West Point cultivates a culture of character growth when staff, faculty, and cadets consistently value, reinforce, support, and pursue character development. In support of that effort, West Point strives for organizational integrity by ensuring all policies, artifacts, and social norms are consistent with the aspirational ideals of living honorably, leading honorably, and demonstrating excellence (United States Military Academy, 2020, p. 14).” It is also stated in the USMA Strategy that the most critical enabler of the West Point Leadership Development System is the ubiquitous culture of character growth (United States Military Academy, 2020).

An integral part of any school or training system’s ability to create a culture of character growth is its leadership and faculty. As Derek Bok (2020), former Harvard University president observed, “Another way in which colleges may have a significant impact on their students’ character is through the example set by the institution and its staff” (p. 66). This idea is also conveyed in the Jubilee Center’s Character Framework for Universities through their claim that character is “caught” via university staff (among others) who help provide the culture, inspirational example, and positive influence that creates the context for character formation (Jubilee Center for Character and Virtues, 2020). As John Locke (1968) states, “nothing sinking so gently, and so deep, into Men’s Minds, as Example” (p. 182).

Not only is it necessary for institutions of higher education dedicated to character formation to have faculty demonstrating good character, but it can also be helpful to have competent teachers of character. While not all members of the faculty (or many) likely have a background in character and virtue formation, they can, however, be taught the basics and can be provided with ideas about integrating character into teaching their own academic discipline. Furthermore, faculty can be given strategies for developing character in their students through one-on-one relationships. Calls for faculty, regardless of academic discipline, to demonstrate good character as examples for their students along with integrating character and virtue formation opportunities and exercises into teaching broadly have been articulated (Bok, 2020; Roche, 2009).

Initial work has been done to help universities develop their faculties’ competence in forming character within their students in the classroom. One framework integrating effective teacher behaviors with character strengths and virtues has been designed (McGovern & Miller, 2008). This framework has been created with four faculty development modules that better enable instructors and teachers to integrate character strengths and virtues into the classroom and teaching environment (McGovern, 2011). Recent work at Wake Forest University using Communities of Practice to increase faculty’s’ ability to integrate character education into a diverse range of classrooms was shown to increase participants’ understanding of the meaning of character education, how to develop character in their students along with how to assess character (Allman et al., 2023).

To date, little work has been done to examine whether faculty development aimed at promoting good character in faculty and increasing faculty character education competence should be tried and whether it would be feasible and acceptable to staff. At USMA, we decided to pilot a faculty development series focused on character formation for members of the Center for Enhanced Performance (CEP). West Point’s CEP offers multiple courses and individual appointments aimed at enhancing cadet performance across all programs, including character, physical, academic, and military. The CEP, composed of three programs (Academic Excellence, Athletic Academic Support, and Performance Psychology), takes a holistic approach to cadet development, bridging the gap between cadets’ past experiences and college expectations as they make the transition to USMA. Specifically, CEP assists cadets in learning to: Develop confidence, summon and maintain concentration, develop the ability to remain calm and composed under pressure, manage time, organize efforts, plan for success, and to read, study, and execute tests with deliberate strategies. CEP was chosen because of the Director’s prioritization of character within the department and the positioning of a character developer within the Center along with the uniqueness of CEP’s dual roles of both teaching and work in one-on-one relationships with cadets. Our aim with this small pilot was to test the feasibility and acceptability of character formation training with faculty.

Methods

Study Sample

The CEP is composed of seven men and 10 women, of whom two are Army officers, and 15 are civilian faculty. There are three specialty programs within the department: the Academic Excellence Program (AEP) has five members who specialize in academic skill development and academic counseling, the Athletic Academic Support Coordinator Program (AASC) has five members who focus their academic advising on USMA’s Corps Squad (NCAA Division 1) population (which is approximately 25% of the Corps of Cadets), and the Performance Psychology Program (PPP) has four members who use applied sports psychology to develop mental skills in cadets. CEP’s faculty range in experience from nearly 30 years of service in the CEP to a few who recently joined the team after completing their graduate schooling. All CEP faculty members teach the RS101: Student Success Course in addition to discipline-specific courses, and all members conduct one-on-one appointments with cadets.

Description of Faculty Development Series

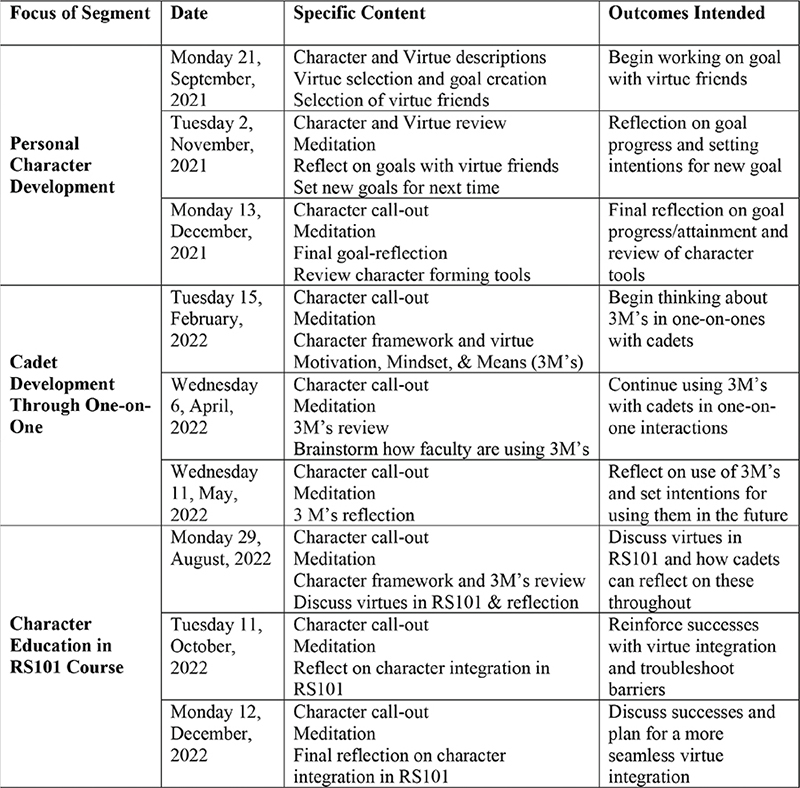

The faculty development series began with a goal of personal character development in the fall of 2021. This segment of the series focused on personal character development for faculty and included basic descriptions of character and virtue, each faculty member selecting a virtue to focus on developing through the semester and proper goal-setting techniques. CEP faculty also selected “Friends of Mutual Accountability” (Lamb et al., 2021), where each faculty member chose two or three friends that would share their goals and support each other’s goal pursuit. The segment also included “Character Call-Outs” where faculty could identify examples of good character they noticed in CEP faculty along with brief Mindfulness Meditation (MM) practice because of its ability to enhance self-regulation (Tang et al., 2015).

The goal of the second segment in the series (spring 2022) was to help faculty learn how to develop cadet character more effectively through one-on-one relationships. We chose to focus on one-on-one relationships because CEP faculty spend a significant amount of time advising cadets on personal performance related matters. “Character Call-Outs” and MM continued in this segment but a shift in focus to cadet development involved strategies to enhance cadets’ Motivation to be a person of character, character growth Mindset, and providing cadets with the Means for character growth (i.e. goal-setting, “Friends of Mutual Accountability,” MM, moral exemplars) also known as the 3M’s framework (Erbe et al., 2023). The goal of this segment was to help faculty consider ways of developing cadets’ character using the 3M’s framework in their one-on-one interactions with cadets.

The goal of the third and final segment in the series was to help faculty more effectively integrate character topics into teaching CEP’s RS101 Student Success Course. The Student Success Course offers cadets an opportunity to engage with learning science and performance psychology strategies to enhance their academic, physical, and leadership performance at USMA. Strategies presented include effective thinking, goal setting, time management, self-regulated learning, concentration, test taking, memory, note taking, and energy management. Through academically engaging activities, this course assists cadets in developing personalized skills and attributes that support thriving along with helping to facilitate a successful transition to USMA. The Student Success Course provides a learning experience that reveals, develops, and builds upon the unique strengths and talents of each cadet.

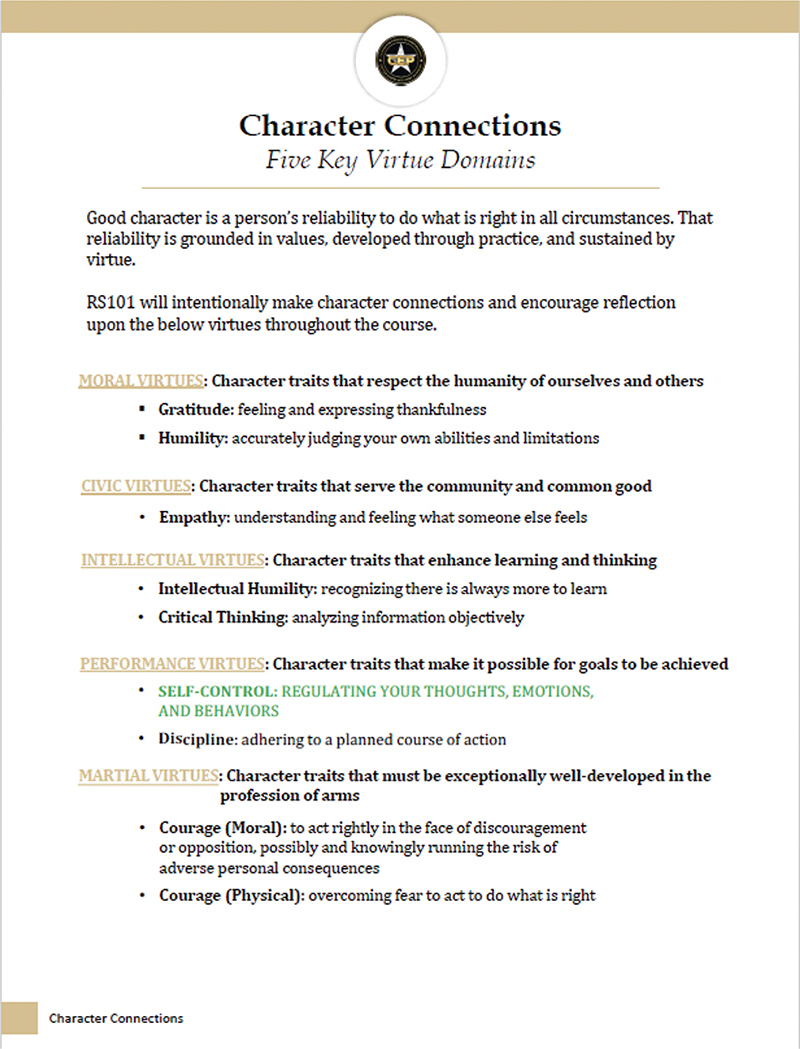

“Character Call-Outs” and MM continued in the series with a shift toward helping faculty consider ways to bring virtues into class discussions and reflections on how course content connected with virtues (see Figure 1 for a list of virtues and definitions used in the course). A detailed description and breakdown of each segment in the faculty development series can be found in Figure 2.

Figure 1

Student Success Course Virtue Definitions

Figure 2

Character Faculty Development Segment Details

Instrument and Analysis

We used a Qualtrics survey that asked the following questions: “How worthwhile was the CEP Character Faculty Development (CFD) (0-Not at all worthwhile to 4-Extremely worthwhile)?” “How much has the CEP CFD helped motivate you to be a person of character (0-None to 4-A great deal)?” “As a result of participating in the CEP CFD, how much has the material helped you see that your character can change, how many more tools do you believe you now have to develop your own character, and how much has your character developed (0-None to 5-A great deal)?” “How useful do you find the following tools for character development (self-monitoring and goal-setting, friends of mutual accountability, mindfulness meditation, moral exemplars) (0-None to 5-A great deal)?” Finally, “As a result of participating in the CEP CFD how much more confident are you in developing cadets’ character and integrating character development into your teaching (0-None to 5-A great deal)?” Our data analyses included examining means and standard deviations for each question. If our means were above zero, then we determined the faculty development series was feasible and acceptable to staff.

Results

Table 1 displays study demographics along with means and standard deviations for each item.

Discussion

Service academies and institutions of higher education interested in developing their students’ character should focus on creating a culture of character growth through developing their faculty’s character and competence. We piloted a faculty development series at USMA for the CEP’s Faculty to determine feasibility and acceptability. Our experience and initial evidence from our small sample suggests that programs like this should be tried and may be feasible and acceptable to faculty.

Other CFD interventions have been developed and tested (Allman et al., 2023; McGovern, 2011; McGovern & Miller, 2008). Our work is consistent with Allman et al. (2023) in showing the feasibility and acceptability of CFD with our results showing faculty finding the faculty development series to be worthwhile and helping faculty to feel confident in developing cadets’ character and integrating character into the classroom. Two unique features of the current faculty development series are the focus on personal character development for faculty and the emphasis on developing cadet character through one-on-one relationships. These components along with the third need further testing with larger samples and more rigorous study methods to determine effectiveness.

Our study was not without limitations. Our small sample size and unique population do not allow for effectiveness determination or the ability to generalize to a larger population within or outside of USMA. Furthermore, only post-assessment data were collected, and without a comparison group, it is impossible to tell whether the results were due to the intervention, or some other experience faculty had at the academy. Lastly, although the aim of this pilot study was to determine feasibility and acceptability of the intervention for faculty participants, one critical impact of the intervention that remains unknown is the effect on cadets. To examine outcomes of faculty character development on cadet character, an experimental wait-list control design could be used. Specifically, half of interested instructors teaching a course should receive the character development intervention with a control condition of interested instructors experiencing faculty development as usual (followed up in the next semester with the character intervention). Cadets in classes with instructors from both groups should be surveyed pre and post intervention on how often character elements were brought up in class and potentially character mindset and motivation outcomes. The two groups should be compared to each other to determine impacts of the intervention.

Although the aforementioned limitations exist, the initial findings from this pilot study indicate that the intervention was feasible (could be effectively delivered) and acceptable to the faculty members and should be tested further for wider spread applicability and effectiveness. A second phase of this intervention, with modifications based on the findings presented here, is planned to begin in the fall of 2023. Future research should also test the impact of the faculty development series in other departments at USMA and at other institutions including both service academies and universities interested in creating a culture of character growth.

Conclusions

Character development programs for faculty aimed at developing both character and competence should be tried and can be feasible and acceptable for faculty. Institutions of higher education interested in creating a culture of character growth can develop, plan, and implement these types of programs for the potential benefit and flourishing of all.

References

| Allman, K. R., Maranges, H. M., & Lamb, M. (2023). Exploring character in community: Faculty development in a university-level community of practice (Manuscript submitted for publication). |

| Bok, D. (2020). Character: Can colleges help students acquire higher standards of ethical behavior and personal responsibility? In Higher expectations: Can Colleges teach students what they need to know in the 21st century? (p. 58). Princeton University Press. |

| Erbe, R. G., Konheim-Kalkstein, Y. L., Fredrick, R., Dykhuis, E. M., & Meindl, P. (2023). Designing a course for lifelong self-directed character growth (Manuscript submitted for publication). |

| Jubilee Center for Character and Virtues. (2020). Character education in universities: A framework for flourishing (pp. 1–12). Jubilee Center for Character and Virtues. |

| Lamb, M., Brant, J., & Brooks, E. (2021). How is virtue cultivated?: Seven strategies for postgraduate character development. Journal of Character Education, 17(1), 81–108. |

| Locke, J. (1968). Some thoughts concerning education. In J. L. Axtell (Ed.), The educational writings of John Locke (pp. 114–325). Cambridge University Press. |

| McGovern, T. V. (2011). Virtues and character strengths for sustainable faculty development. The Journal of Positive Psychology, 6(6), 446–450. https://doi.org/10.1080/17439760.2011.634822 |

| McGovern, T. V., & Miller, S. L. (2008). Integrating teacher behaviors with character strengths and virtues for faculty development. Teaching of Psychology, 35(4), 278–285. https://doi.org/10.1080/00986280802374609 |

| Roche, M. (2009). Should faculty members teach virtues and values? That is the wrong question. Liberal Education, 95(3), 32–37. |

| Tang, Y.-Y., Hölzel, B. K., & Posner, M. I. (2015). The neuroscience of mindfulness meditation. Nature Reviews. Neuroscience, 16(4), 213–225. https://doi.org/10.1038/nrn3916 |

| United States Military Academy. (n.d.). About West Point. https://www.westpoint.edu/about |

| United States Military Academy. (2020). The USMA strategy (pp. 1–24). United States Military Academy. |