PROGRAM/INTERVENTION

Leadership as a Values-Driven System

Christopher P. Kelley, United States Air Force Academy

Matthew M. Orlowsky, United States Air Force Academy

Shane D. Soboroff, United States Air Force Academy

Daphne DePorres, United States Air Force Academy

Matthew I. Horner, United States Air Force Academy

David A. Levy, United States Air Force Academy

ABSTRACT

Leadership is fundamentally a social process. The tendency to view leadership from the unique and private worlds of a leader’s individualized experience is a hindrance to developing effective processes and healthy culture. Leaders in organizations must adapt in response to the changing internal and external ecology in which the organization is nested. The Leadership Systems Model (LSM) offers a paradigm encouraging leaders to embrace a systems perspective. The model utilizes a value-driven human centric approach that focuses on changing elements of organizational structures and processes to align outcomes with organizational values to meet intent. The model recognizes the complexity of organizations, and the multiple roles people play as leaders, followers, and teammates. With this approach, we suggest that leaders can enhance organizational performance and develop a healthy culture by applying their power to systems design, increasing engagement, and continuous improvement.

Keywords: Leadership, Systems, Values, Culture, Power

Citation: Journal of Character & Leadership Development 2024, 11: 301 - http://dx.doi.org/10.58315/jcld.v11.301

Copyright: © 2024 The author(s).

This is an Open Access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/), which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original work is properly cited.

CONTACT David Levy david.levy@afacademy.af.edu

Published: 05 August 2024

Introduction

Leadership is a social process that requires an uncommon understanding of people as well as social and technical systems. More than understanding oneself, effective leadership requires us to manage relationships, design systems, develop procedures, and manage resources in ways that align organizational values with organizational goals (or outcomes). From this perspective, a new paradigm for some, effective leadership includes the advancement of organizational goals through the creation of organizational culture that enhances, rather than degrades, organizational performance. A perspective where leaders seek to understand the interaction between structure, relationships, culture, and motivation shifts the focus from individuals to systems and processes, which are fundamental to modern organizations (Weber, 1978 [1920]). The Leadership Systems Model (LSM) offers an approach to organizational leadership from a systems perspective, as opposed to a reductionistic one. The model is presented in general terms and applied to the leadership development programs at the U.S. Air Force Academy (USAFA) to further illustrate its utility.

The LSM emphasizes the essential need for human-centered design and values-driven strategies to achieve organizational goals within a broader context. The system must be flexible and adjusted to changing ecosystem inputs and required outputs. The LSM captures the internal and external complexity of organizations and can be tailored to the distinctiveness of different organizations and varied organizational components. The desired outcomes at any level consider interactions with the respective environment of interest and are responsive to immediate concerns and demand signals. Within the context of USAFA, the LSM builds upon the core values (integrity, service, and excellence) and holds as intended outcomes “Leaders of Character” who possess a world-class education and are ready to execute the mission, lead people, and manage resources while improving the unit (AFI 1–2).

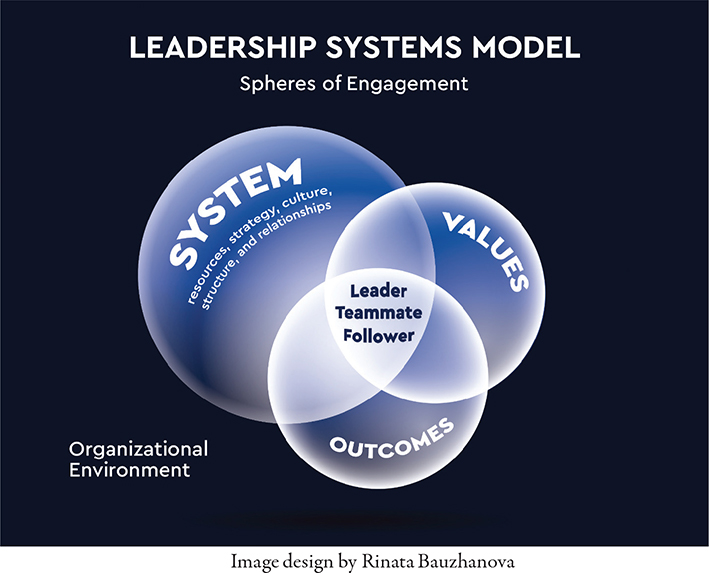

A simplified depiction of the LSM is provided in Figure 1 that can be applied in any organization. It includes the basic elements of a single socio-technical system within a broader ecosystem. Note that the LSM assumes multiple systems exist and interact simultaneously, which are often embedded within larger systems with individuals occupying both concurrent and shifting roles as leader, follower, and teammate depending on the level of analysis. These shifting roles are depicted at the center of the model and the organization is embedded within greater ecosystems (Scott & Davis, 2015).

Figure 1

Leadership Systems Model

Within the LSM, leaders are responsible for structuring formal processes that govern the informal interactions, which create culture and lead to the accomplishment of organizational objectives and outcomes (Li et al., 2024; Maak & Pless, 2006). Culture in turn affects motivation (Mahal, 2009). Applying this model illustrates how leaders’ design efforts can produce both intended and unintended outcomes (Merton, 1968 [1949]; Mintzberg, 1987). As the architect of the system, leaders are responsible for both eventualities. By adopting a broader systems lens, leaders can isolate and address dysfunctional mechanisms and adjust essential processes and policies to ensure congruence with the organizations’ values. Cultural alignment advances motivation, fostering a sense of purpose and direction (Schein, 2010), which helps reinforce and reproduce desired outcomes.

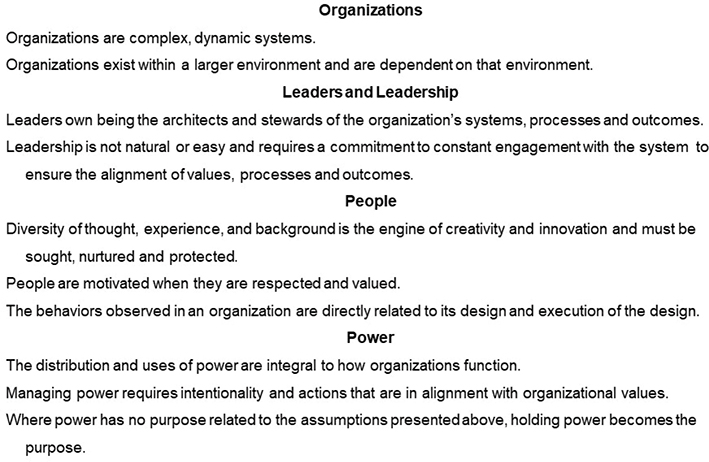

Resting on the assumptions embedded in the model (see Figure 2), the LSM provides guidance about where action (also conceived as power) may be needed to align interests and structure processes to create healthy, productive cultures. The LSM proposes pathways for testing and applying tools to address problems effectively. The LSM affords the broad lens needed to recognize where assumptions about best practices and traditions are either misinformed or maladaptive within the dynamic organizational environment.

Figure 2

Assumptions Embedded in the Leadership Systems Model

Systems thinking stands upon the emergence of strategy, structure, and relationships; as well as the consequences of communication and control (Checkland, 2000). Through interactions in organizational structure and processes, various properties and values become esteemed by members and create subsystems to communicate and influence behavior, intentionally or not (Checkland, 2000; Weber, 1978 [1920]). This dynamic interaction requires leaders to develop and apply strategies that foster a shared perspective, which informs intentions and action (Mintzberg, 1987). A strategic vision of the organization aligns its design so that “culture is [becomes] our learned solution to making sense of the world, to stabilizing it, and to avoiding the anxiety that comes with social chaos” (Schein, 2010). In that vein, culture then is the organizational equivalent of character, and it must be taught, developed, and reinforced. This characterization and systems approach is vital if USAFA is to fulfill its charter to generate a core group of innovative leaders capable of critical thinking to “exert positive peer influence to convey and sustain …traditions, attitudes, values and beliefs essential to the long-term readiness and success of the Military Services” (DoDI 1322.22, Military Service Academies, para 3b). Collectively, LSM conceptualizes a system as a way to scale values for organizational excellence.

Thus, the LSM builds upon USAFA’s Leader of Character Framework,1 which guides USAFA’s developmental approach, by emphasizing alignment of organizational and individual values as primary components of leadership. The LSM, therefore, is a process model that aims to achieve outcomes that are aligned with organizational values. It implements “one of the most vital aspects of leadership: it cannot influence people ‘downward’ on the need or value hierarchy without a reinforcing environment” (Burns, 1978, p. 44). The model consists of three intersecting Spheres of Engagement for consistent individual and organizational level inputs. The three Spheres of Engagement (system, values, and outcomes) represent entry points for leadership actions. The spheres can be understood as areas that leaders need to actively assess and engage for both organizational maintenance and organizational change.

The first and largest sphere is the systems sphere, which visually depicts the importance of understanding how resources, strategies, structure, culture, and relationships drive outcomes and reinforce organizational values. When an organizational system is not producing desired results, leaders ought to engage with the System sphere first to consider and implement changes. Outputs from dysfunctional systems also have negative effects on the broader ecosystem, future inputs, and the health of the organization. For example, if an organization’s culture is out of alignment with its values, assessing practices and relationships for their contributions to culture is prudent. A leader might employ a tool such as a zero-based budget philosophy to analyze whether these aspects of the organization support or detract from the desired culture. Are there places where a hierarchy is emerging that values something other than what the organization desires? What actions does the architect need to take to arrest that emergence to keep individual competition from hijacking organizational values and outcomes while fulfilling organizational members’ needs? What must remain paramount for leaders is that outcomes are connected to our purpose, they tell us why we exist and what we are trying to do.

The second sphere, values, represents the importance of shared beliefs. These beliefs include both legitimate organizational goals and the accepted means for achieving those goals. The specific values within the sphere are of less significance than the interplay between values, structure, and outcomes. According to the LSM, values can be seen as both the “price of admission” for engaging in leadership as well as what is to be developed and maintained through engagement with the system. While leaders are emphasized, the model applies to all organizational members. Managing power requires intentional structure to create a culture based on organizational values, reducing ambiguity of purpose (Weick, 2001). When the values of the organization do not determine how power should be applied, those with power tend to apply it to meet their own purposes or self-interest, often inconsistent with shared goals (Fast et al., 2012). Here again, congruency of values with organizational structure and outcomes ensures consistent decision-making and behavior throughout the organization, fostering enhanced satisfaction and retention (Schein, 2010).

The third sphere is the outcomes sphere. It describes the organization’s purpose and reason for existence. Systems produce what they are designed to produce and high functioning organizations have leaders that align organizational outcomes with their values (Li et al., 2024). Organizations that overly focus on efficiency and performance metrics may sacrifice effectiveness as outcomes emerge to replace stated values and purpose, leading to unintended consequences (John et al., 2023). Hence, the values of the organization act as the guiding principles of action (Weber, 1978 [1920]).

This leadership systems approach fosters an understanding of a leader’s responsibility for the structure, resources, relationships, culture, and resulting motivations that underpin success and long-term readiness. To bring this about, systems leaders develop influence by earning the respect of followers. This is accomplished through essential interpersonal skills and tools to manage power, assuring the leader’s competence in their areas of specialization and their leadership duties. By modeling these practices, leaders serve as the prototypes for values and behaviors they want others to adopt. Managing power requires a keen understanding of context and people, recognizing how holding and applying power affects people, perceptions, and processes within the system. While power is a necessity for accomplishing tasks and essential for the formal structure of organizations (Blau, 1986; Pfeffer & Salancik, 2006), effective leaders remain aware of how it may alter their own and others’ perceptions in dysfunctional ways, despite the leader’s best intentions (Magee & Galinsky, 2008). Power can be utilized for organizational design and change (Blau, 1986; Pfeffer & Salancik, 2006), but we propose it is most effective when applied to change structure and processes rather than to coerce compliance through threat of punishment or enticing compliance through promised rewards.

With this framework in mind, we recognize two lines of leadership engagement and growth—individual and organizational—where both are important and interrelated. From the individual standpoint, the LSM presented here focuses on the importance of embracing values and behaviors, such as humility, integrity, perspective taking, and an ability to communicate effectively, that make a person better suited to perform the role of a leader. Yet, for the organization, it is just as important to understand how to develop leadership systems aligned with theory and practice that explain the nature of organizations and the behavior of people within them. The synergy between these two lines of development support a culture that improves organizational performance and reduces undesired outcomes, thereby enhancing achievement of organizational goals.

The LSM illustrates how action is often context driven and that leaders can and do apply efforts to various spheres to bring about desired change. It emphasizes the second and third order effects of decisions and processes. It makes evident that the values sphere will directly impact elements of the systems sphere, and so outcomes as well as the broader organizational ecosystem. If a culture change is desired, applying energy to the elements of the systems sphere is the most impactful approach to culture change to reinforce values and cultivate shared beliefs. During times of crisis, focus and energy is often directed and applied to the outcomes sphere through increased demands on organizational members and on system components, increasing stress without changing the processes that produce results. This may yield short-term outcome gains, but the model suggests it would be wise to make changes to the systems sphere if long-term outcome changes are desired. Notice, also, that the systems sphere is the largest and implies that it should be a focal point for almost any leadership initiative.

Conclusions

By using the LSM, leaders can more effectively recognize persistent problems to develop solutions that address root causes. When outcomes do not align with organizational values, the model directs leaders’ attention to structures and processes, where otherwise there is often a tendency to over-focus on inputs or make individualistic attributions. Instead of assuming that problems lie with specific people or a lack of resources, a leader’s attention is shifted to situational factors within their control that are motivating unintended behaviors. When the behavior of followers and teammates are not aligned with goals, the model assumes actors’ best intentions and shifts responsibility to leaders to design procedures and processes—to identify false assumptions, test alternatives, and implement systems changes to overcome persistent problems.

The LSM can aid USAFA as it continuously improves and strengthens its focus on developing leaders of character that can deliver the clear results demanded by the Air Force and Space Force. The LSM fulfills USAFA’s congressional charter by implementing a leadership development system that motivates graduates to seek leadership responsibilities with a keen ability to think critically, decide wisely, and act decisively while maintaining a culture where leaders of character exert positive peer influence through their character foundation (DoDI 1322.22). In this capacity the LSM focuses on leaders as the architects of systems rather than on individual leader attributes. Within the LSM cadets can apply a series of tools and gain proficiency through their 4-year USAFA leadership development experience. Introduced in the first year, cadets can employ the LSM throughout their tenure as followers, teammates, and leaders providing ample practice in varying contexts to hone their leadership ability in increasingly complex organizational environments. Thus, the LSM frames a leader’s lifelong journey of study, practice, and reflection, encouraging a holistic and nuanced appreciation of the complexity of oneself and the teams they lead as made up by, and making up, the systems they inhabit.

References

| Air Force culture: Commander’s responsibilities, Air Force Instruction 1–2. (2014). https://www.af.mil/Portals/1/documents/csaf/afi1_2.pdf |

| Blau, P. (1986). Exchange and power in social life. Routledge. |

| Burns, J. M. (1978). Leadership. Harper & Row. |

| Checkland, P. (2000). Soft systems methodology: A thirty year retrospective. Systems Research and Behavioral Science, 17(S1), S11–S58. https://doi.org/10.1002/1099-1743(200011)17:1+%3C::AID-SRES374%3E3.0.CO;2-O |

| Fast, N. J., Halevy, N., & Galinsky, A. (2012). The destructive nature of power without status. Journal of Experimental Social Psychology, 48, 391–394. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jesp.2011.07.013 |

| John, Y. J., Caldwell, L., McCoy, D., & Braganza, O. (2023). Dead rats, dopamine, performance metrics, and peacock tails: Proxy failure is an inherent risk in goal-oriented systems. Behavioral and Brain Science, 47, e67. https://doi.org/10.1017/S0140525X23002753 |

| Li, X., Chen, G., & Shen, R. (2024). Steering the intangible wheel: Chief executive officer effect on corporate cultural change. Organization Science, ahead of print. https://doi.org/10.1287/orsc.2022.17210 |

| Maak, T., & Pless, N. (2006). Responsible leadership in a stakeholder society—A relational perspective. Journal of Business Ethics, 66, 99–115. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10551-006-9047-z |

| Magee, J., & Galinsky, A. (2008). Social hierarchy: The self-reinforcing nature of power and status. Academy of Management Annals, 2(1), 351–398. https://doi.org/10.5465/19416520802211628 |

| Mahal, P. (2009). Organizational culture and organizational climate as a determinant of motivation. IUP Journal of Management Research, 8(10), 38–51. |

| Merton, R. K. (1968 [1949]). Social theory and social structure. Free Press. |

| Military Service Academies, Department of Defense Instruction 1322.22. (2023). https://www.esd.whs.mil/Portals/54/Documents/DD/issuances/dodi/132222p.pdf?ver=YWqWRrTsiDM6n8j-SkCKAA%3d%3d |

| Mintzberg, H. (1987). The strategy concept I: Five Ps for strategy. California management review, 30(1), 11-24. |

| Pfeffer, J. (2022). 7 Rules of power: Surprising—But true—Advice on how to get things done and advance your career. BenBella Books. |

| Pfeffer, J., & Salancik, G. (2006). External control of organizations–resource dependence perspective. In J. Miner (Ed.), Chapter 19 Organizational behavior 2. Routledge. |

| Schein, E. H. (2010). Organizational culture and leadership (Vol. 2). John Wiley & Sons. |

| Scott, W. R., & Davis, G. (2015). Organizations and organizing: Rational, natural and open systems perspectives. Routledge. |

| Weber, M. (1978 [1920]). Economy and society. University of California Press. |

| Weick, K. (2001). Making sense of the organization. Blackwell. |

Footnote

1. https://www.usafa.edu/app/uploads/21st-Century-LoC-Final-March-2021.pdf