RESEARCH

The Leader Rating Gap: How Leaders Rate Their Subordinate Leaders

Everett Spain , United States Military Academy

, United States Military Academy

Joel Cartwright , United States Military Academy

, United States Military Academy

Kate Conkey , United States Military Academy

, United States Military Academy

Lolita Burrell , United States Military Academy

, United States Military Academy

ABSTRACT

This study investigates a paradox in leadership assessment, which we term the Leader Rating Gap (LRG). Through content analysis of interviews with 25 West Point cadets and tactical officers, we found that raters primarily cited influence behaviors when describing great leadership in general. However, when evaluating their own subordinate leaders’ job performance, raters emphasized individual performance behaviors over influence behaviors. These findings have implications for leadership development and assessment practices in military and civilian organizations, highlighting the need for organizations to align their leadership evaluation criteria with desired leadership behaviors and outcomes.

Keywords: Performance reviews, Evaluations, Ratings, Leadership, Followership, Influence

Citation: Journal of Character & Leadership Development 2024, 11: 314 - http://dx.doi.org/10.58315/jcld.v11.314

Copyright: © 2024 The author(s). This is an Open Access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/), which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original work is properly cited.

CONTACT Joel K. Cartwright joel.cartwright@westpoint.edu

Published: 5 December 2024

Introduction

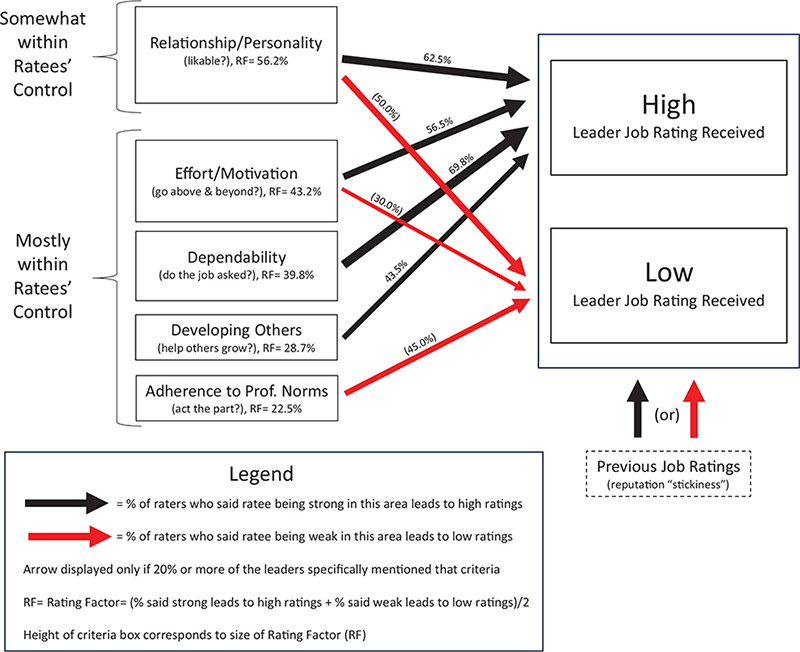

They say great leadership is hard to define, but we sure know it when we see it. Or do we? Applying content analysis to individual interviews of 25 West Point cadets and tactical officers illuminates a related paradox. When raters were asked to describe how they know when someone else really “has it” as a leader, they primarily cited influence behaviors. Yet, when these same raters were asked to describe the criteria they use to assess the job performance of subordinates, almost all of whom were in leadership roles themselves, raters cited evaluating individual performance behaviors more than influence behaviors, a phenomenon we name the Leader Rating Gap (LRG) depicted in Figure 1. Specifically, raters cite assessing their subordinate leaders on, in order of decreasing frequency: relationship/personality, effort/motivation, dependability, focus on the development of others, and adherence to professional norms. Additionally, we found that the previous job ratings subordinate leaders receive are “sticky,” as they influence the subordinates’ current job ratings.

Figure 1

How Leaders Rate Their Subordinate Leaders

Identifying Someone Who Is (Could Become) a Great Leader

Organizations have long been concerned with assessing the leadership ability and potential of their leaders and future leaders, hereafter “subordinate leaders” (Marshall-Mies et al., 2000). There have long been debates on which qualities make great leaders (Bass, 1985; Kirkpatrick & Locke, 1991) and limitations in the ability to accurately assess desired leadership skills and behaviors (Kolb, 1995; Yukl & Van Fleet, 1992). Additionally, even when there is consensus on leader qualities and assessment tools, raters’ biases and environmental influences can affect their evaluation of their subordinate leaders’ performance and potential.

Leaders’ Influence on Others

Leadership is generally seen as behaviors that inspire, influence, and motivate performance in others (Bass & Riggio, 2006; Northouse, 2018). Effective leaders mobilize followers, prioritize subordinate needs, and foster a positive service culture (Heifetz et al., 2010; Linden et al., 2014; Maxwell & Dornan, 2006). This selflessness is central to ethical and transformational leadership, where leaders act as role models, transforming followers’ values and beliefs (Bass, 1999; Hendrix et al., 2015; Mayer et al., 2012). Yukl (2012) identifies task, relations, and change-oriented behaviors as key to organizational influence. Additionally, strong leader character links to greater organizational commitment, satisfaction, work group performance, and organizational citizenship behaviors (Hendrix, 2015). Indeed, effective senior leadership, which includes ethical and transformational practices, correlates with positive outcomes like organizational performance, employee engagement, and adaptability (Church et al., 2021).

Influential Leader Traits and Behaviors

When describing effective leadership, scholars cite the importance of influence behaviors, individual performance traits, and effective followership, though they do not agree on which are most important (Feller, 2016; Giles, 2016). Examples of important influence behaviors and leader traits include leader vision, inspiration, empathy, and trustworthiness (Bennis, 1989) and emphasize listening, persuasion, stewardship, and commitment to growth (Spears, 2010). Traits like humility suggest successful leaders focus on others’ interests, fostering strong relationships, work engagement, and likability (Beissner & Heyler, 2020; Wortman & Wood, 2011). Social intelligence, the ability to understand and manage oneself and others (Thorndike, 1920), and emotional intelligence are also said to be crucial to effective leadership (Goleman, 2011; Goleman & Boyatzis, 2008), as is being attuned to social contexts (Huang, 2020). Additionally, social judgment skills become more important as leaders advance and handle more complex and ambiguous problems (Mumford et al., 2000). Similarly, Bartone et al. (2002) found that social judgment skills and Big Five traits like conscientiousness and agreeableness enhance leader performance. Since conscientiousness includes dependability and perseverance, and agreeableness involves selflessness and cooperativeness (Barrick & Mount, 1991; Witt, 2002), leader traits and their influence behaviors can be closely related. Other authors have stressed the importance of the example the leader sets for others (Spain et al., 2021) and the significance of a leader’s character on their organizations (Spain et al., 2022).

Furthermore, some of the traits and behaviors that make effective leaders also make effective followers (Riggio et al., 2008; Uhl-Bien et al., 2014). Effective followership can be defined as deliberately executing the vision of the leader (Slager, 2019). Indeed, effective followers are proactive, responsible, and problem solvers, similar to good leaders (Hamlin, 2016). McCallum (2013) notes that most people are followers more often than leaders and outlines similar qualities of followership: strong self-management, commitment to the organization, optimal impact focus, courage, credibility, and honesty. Implicit followership theory describes ideal followers as team players, loyal, productive, and engaged (Junker & Van Dick, 2014). Since almost all leaders are also followers, when leaders are evaluated for their performance, raters may evaluate their subordinate leaders on both their influence behaviors and their followership behaviors.

Leadership Assessment

Assessing leadership is crucial for organizational performance, yet objective evaluation is challenging. For example, inaccuracies in performance appraisals stem from unclear roles and goals (Anderson & Stritch, 2015), imperfect metrics (Behn, 2003), judgment errors, and biases such as the halo effect and implicit prototypes (Bowman, 1999; Junker & Van Dick, 2014; Schyns & Meindl, 2005). Biases can distort evaluations, as raters may focus on one positive trait or prioritize unconscious schemas. Additionally, rater-subordinate similarities can positively skew evaluations (Schraeder & Simpson, 2006). Evaluating individuals with diverse skills complicates assessments, as past successes may not guarantee future success (Finkelstein et al., 2018).

The performance appraisal system used by organizations also affects how raters assess subordinates. A forced-distribution rating system (FDRS), used by organizations such as the U.S. Army to evaluate its officers and the United States Military Academy (USMA) to evaluate its cadets (US Army, 2019; USMA, 2022), requires raters to differentiate between strong and weak performances, aiming to improve accuracy and promote honesty (Stewart et al., 2021). This helps prevent leniency and centrality biases, where raters give overly generous or moderate ratings to avoid conflict (Berger et al., 2013; Schleicher et al., 2008). A FDRS typically categorizes subordinates into above-average, average, and below-average, with corresponding incentives such as raises and promotions, which can undermine teamwork and create feelings of injustice (Moon et al., 2016). Combining FDRS with other appraisal challenges and desired leader traits and behaviors leads to our first series of questions of our exploratory research:

RQ 1A: What traits and behaviors do raters look for when identifying a great leader in general?

RQ 1B: What traits and behaviors do raters actually use when differentiating the performance of their subordinate leaders?

RQ 1C: Are the answers to 1A and 1B the same?

Since an FDRS effectively makes a rating system into a competition for high ratings, it is important to consider what else may influence ratings other than the ratees’ influence behaviors and individual performance. One possibility is that leaders’ previous job ratings, operationalized as their professional reputation, will influence their current rating. Scholars have shown that past performance is a primary data point for identifying high-potential talent, referred to as “high potential,” “future leader,” “crown jewel,” or “shining star” (Church et al., 2021), and these stars excel in their roles, receive higher regard and rewards, are often more visible due to higher visibility projects and responsibilities (Groysberg et al., 2008), and are disproportionately more valuable and productive than average workers (Ernst & Vitt, 2000; Hunter et al., 1990; Narin & Breitzman, 1995). Since past performance is a predictor of future performance (Lawler, 2017), raters may be tempted to take the cognitive shortcut of allowing subordinate leaders’ previous rating(s) to influence their current rating. This leads to our final research question:

RQ 2: Do leaders’ previous job ratings influence their current rating (stickiness)?

Method

Design

We conducted a qualitative content analysis using semi-structured interviews. Subjects included current and former West Point cadets and tactical officers.

Semi-Structured Interview Development

The principal investigator developed the initial interview guide and preliminary semi-structured interviews to validate the guide, interview techniques, and technology, focusing on the process of assigning the military development (MD) grade. The MD grade, a weighted average of ratings from military officers and upper-class cadet supervisors, reflects a cadet’s overall job performance. Half of the MD grade comes from a military tactical officer supervisor, and the other half from two-to-three upper-class cadet supervisors, and it is given at the end of each semester and summer training period (Lewis et al., 2005). As every tactical officer and cadet rater is necessarily in a leadership position, and every rated cadet was serving in a leadership position or soon will be (e.g., a freshman) (USMA, 2018), the MD grade could be considered a “leadership grade,” though this rephrasing has not been formally studied for validation.

The preliminary interviews included one current cadet, one current tactical officer, and one former cadet and covered themes such as institutional expectations for grading, how cadets graded each other, perceived grading criteria, and the relevance of MD grades predicting officer performance. Participants were also asked about other topics they wished to discuss. These interviews revealed the potential influence of other grades (academic and physical performance/grade point average [GPA]), leading to the refinement of the initial questions.

Participants

We conducted 25 interviews using a purposeful convenience sample, including 12 current West Point cadets (two women and 10 men) equally divided between the top and bottom 20% of their class: two first-year students, two sophomores, four juniors, and four seniors whose job performance was rated 11 times throughout their four years. Additionally, we interviewed eight tactical officers (all men). These included four current tactical officers and four who served in the role from 1996 to 2005, who have all rated their cadets. We also interviewed five alumni (one woman and four men), from classes spanning from 1992 and 2004, with little suspected structural or cultural change to the rating system during the aforementioned periods. These demographics were generally consistent with the cadet and tactical officer population at the time of data collection.

Semi-Structured Interviews

The principal investigator conducted the interviews. Twenty of the interviews were conducted by phone, and five were in person. Each interview lasted between 30 and 75 min, with an average duration of 45 min. All interviews were recorded using a smartphone and transcribed verbatim using a private transcription service.

Ethics

Each participant provided consent at the beginning of the interview. The United States Military Academy’s Human Research Protection Program approved the study.

Data Analysis

Code Development

Our exploratory study employed a rigorous qualitative content analysis methodology using MAXQDA 2022 software (VERBI Software, 2021), adhering to the iterative abstraction and interpretation framework delineated by Lindgren et al. (2020). Each of the four researchers independently coded the same set of interviews, followed by weekly team meetings dedicated to discussing, refining, and revising the emerging codes. This collaborative approach ensured a thorough examination of the data, with the iterative process persisting until the team collectively determined that no additional codes were emerging.

During this process, we realized that coding interviews in their entirety might allow the context of one question to influence the coding of subsequent questions. To address this, we adapted our strategy for the second coding phase by segmenting interviews into smaller units based on individual questions. Each question was then coded in isolation by a designated researcher, mitigating the risk of cross-question influence and ensuring a more focused analysis. Note that this method does not require or support an opportunity to test interrater reliability.

Analysis

Regular team meetings remained crucial, providing a platform to discuss new codes and ensure alignment across all questions. After the detailed coding phase, the team synthesized and organized the codes into broader thematic categories, establishing parent codes while retaining detailed subcodes. As an example, to address our first research questions, we coded the responses to questions about why a leader gave a subordinate the MD grade of “A” alongside the responses to questions about what makes a great leader. This meticulous, iterative alignment and theme development process continued until the team reached consensus on the final set of codes and their thematic structure. Once all responses were coded, we used MAXQDA to retrieve the code frequencies.

Results

What Makes a Great Leader, and How Does a Military Development Grade of “A” Compare?

What do raters say identify great leaders?

Several themes emerged within the responses regarding how a respondent knows when one cadet “has it” as a great (future) leader and another does not (see Table 1). By far, the theme that occurred most frequently of those who responded (n = 21) was the influence on others, with 90.5% of respondents mentioning that that influence on others was integral in being a great leader. Additionally, various emerging leadership traits and behaviors, such as initiative, confidence, and going the extra mile, were mentioned by more than half (61.9%) of those who responded.

What criteria did raters use when giving a military development (leadership) grade of “A”?

Themes that emerged from at least half of those that responded (n = 22) to the question regarding what factors trigger an MD grade of “A” included individual performance (72.7%), followership (72.7%), influence on others (68.2%), and emerging leadership traits and behaviors (63.6%). Note that “influence on others” was only the third most frequently mentioned criterion.

Perceptions of Military Development Grade Influences

Table 2 presents respondents’ identified leader traits and behaviors and the frequency of these traits and behaviors (or absence in the instances of low MD grades) with each letter grade on a spectrum from “A” to “F,” excellence to failure.

Excellent “A” military development grade

As seen in Table 2, for those that responded (n = 23) to the influence of awarding an MD grade of “A” when analyzed with the codes developed for the MD grade-specific questions, responsible and dependable (69.6%), social skills, such as relationship/personality (69.6%), effort/motivation (56.5%) were the top three themes that arose.

Average “B” military development grade

Effort/motivation (75.0%) stood out from other themes within the influence of an MD grade of “B” of those that responded (n = 24) and was the only theme that emerged from at least half of the respondents.

Below average “C” military development grade

For those who responded (n = 20), themes influenced by an MD grade of “C” were less frequent than “A” or “B” grades and given either in a negative context or in the absence of the behavior. The most frequently mentioned theme was (poor) relationship/personality (50.0%), with no other theme identified within at least half of the respondents.

Poor “D” or “F” military development grade

Like the “C” MD grade responses, there were not many mentions of “Ds” or “Fs” in responses and those themes that emerged were negative. However, the theme identified by more than half of the respondents was (poor) relationship/personality (57.1%).

How Do Leaders Differentiate the Performance of Their Subordinate Leaders?

The themes of the interviewees’ (n = 25) responses to questions about how they evaluated subordinate leaders across the range of possible ratings were grouped into five themes. To represent the average likelihood of interviewees referencing that theme when describing a highly rated (“A” or “B”) or lower performing (grades “C,” “D,” or “F”) cadet, we created the variable “Rating Factor” (RF), calculated by adding the percentage of interviewees who said that the presence of that factor leads to high rating to the percentage of interviewees who said the absence of that factor leads to low rating, divided by two. These themes and their corresponding RFs include the ratees’ relationship/personality (RF = 56.2%), effort/motivation (RF = 43.2%) dependability (RF = 39.8%), developing others (RF = 28.7%), and adherence to professional norms (RF = 22.5%). Notably, the only influence (i.e., leadership-related) factor in the top five is “developing others,” coming in as the fourth priority.

Military-Grade Stickiness

Participants were asked whether cadets are able to move their MD grades up or down over time (n = 23) or were their current MD grades dependent on previous ones (i.e., were they “sticky”). The majority responded that they believe that the MD grade is sticky (91.3%) and many cited that initial impressions play a role in that stickiness (42.9%).

As a note, in our analysis, we did not see differences in the responses of our two freshmen (future leaders) from the responses of our 10 upper-class cadets (current leaders) nor did we see significant differences between our tactical officers and cadets. Therefore, we did not include that further in this project.

Discussion

This research supports the presence of what we call the LRG, the unexpected difference between how supervisors (raters) describe great leadership (i.e., primarily influence behaviors) and how they actually rate their subordinate leaders (i.e., primarily individual performance). Further, it presents the criteria that raters, perhaps unconsciously, use to formally evaluate their subordinate leaders. In order of most influential to least so, these include the raters’ perceptions of their ratees’ 1) relationship/personality, 2) effort & motivation, 3) dependability, 4) focus on developing others, and 5) adherence to professional norms.

Since almost all leaders are both followers and leaders, it is possible that raters’ expectations of their subordinates’ ratio of influence-behaviors to individual performance change over time. For example, a USMA cadet team leader is typically a 19-year-old sophomore who supervises either one or two 18-year-old freshmen cadets, while a regimental commander is typically a 21 year-old senior, has had at least two additional years of leadership experience, and supervises 1,100 other cadets from all four classes. Perhaps, on average, raters’ expectations of team leaders are appropriately weighted toward individual performance, whereas raters’ expectations of regimental commanders are more weighted toward their influence behaviors.

Yet, overall, this paper’s findings can be discouraging for an organization’s leadership presence and quality. Even though most organizations have many supervisory positions, since the LRG may predict that leaders will be rated according to their individual performance, these same leaders are less incentivized to supervise and develop their subordinates. The research also showed how job ratings are “sticky” in that previous high performers are potentially unfairly bolstered in future job ratings. Similarly, previous low performers may have difficulty increasing their ratings in proportion to greater performance. Considering these initial findings, we offer several recommendations.

First, to incentivize leaders to spend their limited resources influencing others, organizations should (re)define their formal leader job evaluation criteria to prioritize influence behaviors over individual performance behaviors. These organizations will likely need to determine what right looks like and establish some oversight/control to encourage rater adherence to the formal criteria, as old habits often die hard.

Second, organizations should deliberately educate their leaders on their likelihood of having cognitive biases, including the propensity for them to reward their subordinate leaders’ individual performance over their influence behaviors, the propensity to value the ratee’s relationship/personality (i.e., social skills) over both the ratee’s effort and dependability, and the assumption that the ratee’s current performance is likely similar to their performance during previous rating periods. Following the protocol of the U.S. Army’s new command assessment programs, organizations could ensure to conduct a centralized rater calibration exercise prior to the start of a significant evaluation rating period (such as the end of the calendar year) while also holding brief anti-bias refresher training for raters each morning during that period (Spain, 2020).

Third, to build confidence in their organization’s rating system, senior leaders should consistently and regularly assess it, including annually presenting a report on it to their leaders at all levels. This report should address whether the behaviors measured in their current leader rating system predict leader success, subordinate performance, and organizational outcomes in the short-, medium-, and long-term future. The information, organizational humility, and transparency communicated by this annual report can build leaders’ confidence in their organization and its rating system.

Fourth, many organizations can struggle to decide what criteria to prioritize when choosing which leaders to select for promotion. Individual performance, such as technical skills in structuring complex financial products or maintaining a fleet of military helicopters, can be enormously valuable for an organization. Acknowledging that all talented employees are not capable of or interested in being effective supervisors, organizations may need some members of its talent pipeline to focus on technical knowledge (and individual performance). In contrast, organizations may need other members to focus on developing others (and group performance). Therefore, organizations should consider building separate but similarly attractive career paths for leader-track and technical-track employees. This would be a significant change for the U.S. military and other organizations who currently expect almost all of their senior employees to supervise others.

Finally, there likely is validity to wanting individual performance behaviors in subordinate leaders, especially since leaders’ example alone can create positive motivation in followers. Perhaps organizations now emphasize a particular definition of great leadership that is too narrowly focused on influencing others, whereas a better definition of great leadership may also require both social skills and individual performance skills.

Limitations and Future Research

Although this study addresses ratings of subordinate leaders from multiple perspectives, the sample was selected based on convenience (USMA.) Additionally, while this study was exploratory in nature, the small sample size limits the generalizability to the operational Army or for civilian institutions. Also, the data are just over 10 years old, so adding and analyzing additional interviews could add validity to findings.

Another potential limitation is that the ratings studied are based on a forced distribution system, which means that leaders are constrained in the range of ratings they can give. This constraint may result in individual attributes/accomplishments becoming more salient when deciding who will achieve high ratings. Thus, there are potential disconnects between what attributes/accomplishments leaders say are important and what attributes/accomplishments they actually reward when rating current and future leaders.

Additionally, there are very different expectations of subordinate leaders who lead small groups (e.g., one to eight people, such as USMA team or squad leaders) than subordinate leaders who lead larger groups (e.g., 30 to 1,100 people, such as USMA platoon leaders or regimental commanders). Therefore, future research might focus on unpacking those differences and whether it is worrisome.

Though some civilian organizations also use a forced distribution rating system, future research, including replication with a more representative sample, is suggested to understand if a similar leader rating gap exists for civilian employees (Rainford, 2023; Williams et al., 2021). Also, using a larger sample that includes quantitative measures in addition to qualitative measures would provide a more comprehensive examination and understanding of leader ratings.

References

| Anderson, D. M., & Stritch, J. M. (2016). Goal clarity, task significance, and performance: Evidence from a laboratory experiment, Journal of Public Administration Research and Theory, 26(2), 211–225. https://doi.org/10.1093/jopart/muv019 |

| Barrick, M. R., & Mount, M. K. (1991). The big five personality dimensions and job performance: A meta-analysis. Personnel Psychology, 44(1), 1–26. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1744-6570.1991.tb00688.x |

| Bartone, P. T., Snook, S. A., & Tremble, T. R. (2002). Cognitive and personality predictors of leader performance in West Point cadets. Military Psychology, 14(4), 321–338. https://doi.org/10.1207/S15327876MP1404_6 |

| Bass, B. M. (1985). Leadership: Good, better, best. Organizational Dynamics, 13(3), 26–40. https://doi.org/10.1016/0090-2616(85)90028-2 |

| Bass, B. M. (1999). Two decades of research and development in transformational leadership. European Journal of Work and Organizational Psychology, 8(1), 9–32. https://doi.org/10.1080/135943299398410 |

| Bass, B. M., & Riggio, R. E. (2006). Transformational Leadership (2nd ed.). Lawrence Erlbaum Associates. |

| Behn, R. D. (2003). Why measure performance? Different purposes require different measures. Public Administration Review, 63(5), 586–606. https://doi.org/10.1111/1540-6210.00322 |

| Beissner, L., & Heyler, S. (2020). The value of leader humility in the military. Journal of Character and Leadership Development, 7(1), 41–53. https://jcldusafa.org/index.php/jcld/article/view/104 |

| Bennis, W. G. (1989). On becoming a leader (First Edition, p. 240). Basic Books. ISBN: 978-0-465-01408-8 |

| Berger, J., Harbring, C., & Sliwka, D. (2013). Performance appraisals and the impact of forced distribution – An experimental investigation. Management Science, 59(1), 54–68. https://doi.org/10.1287/mnsc.1120.1624 |

| Bowman, J. S. (1999). Performance appraisal: Verisimilitude trumps veracity. Public Personnel Management, 28(4), 557–576. https://doi.org/10.1177/009102609902800406 |

| Church, A. H., Guidry, B. W., Dickey, J. A., & Scrivani, J. A. (2021). Is there potential in assessing for high-potential? Evaluating the relationships between performance ratings, leadership assessment data, designated high-potential status and promotion outcomes in a global organization. The Leadership Quarterly, 32(5), 101516. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.leaqua.2021.101516 |

| Ernst, H., & Vitt, J. (2000). The influence of corporate acquisitions on the behaviour of key inventors. R&D Management, 30(2), 105–120. https://doi.org/10.1111/1467-9310.00162 |

| Feller, T. T., Doucette, W. R., & Witry, M. J. (2016). Assessing opportunities for student pharmacist leadership development at schools of pharmacy in the United States. American Journal of Pharmaceutical Education, 80(5), 79. https://doi.org/10.5688/ajpe80579 |

| Finkelstein, L. M., Costanza, D. P., & Goodwin, G. F. (2018). Do your high potentials have potential? The impact of individual differences and designation on leader success. Personnel Psychology, 71(1), 3–22. https://doi.org/10.1111/peps.12225 |

| Giles, S. (2016). The most important leadership competencies, according to leaders around the world. Harvard Business Review, 15(3), 2–6. https://hbr.org/2016/03/the-most-important-leadership-competencies-according-to-leaders-around-the-world |

| Goleman, D. (2011). Leadership: The power of emotional intelligence, First Edition (p. 117) More Than Sound. ISBN 978-1-934441-17-6 |

| Goleman, D., & Boyatzis, R. (2008). Social intelligence and the biology of leadership. Harvard Business Review, 86(9), 74–81, 136. https://hbr.org/2008/09/social-intelligence-and-the-biology-of-leadership |

| Groysberg, B., Lee, L. E., & Nanda, A. (2008). Can they take it with them? The portability of star knowledge workers’ performance. Management Science, 54(7), 1213–1230. https://doi.org/10.1287/mnsc.1070.0809 |

| Hamlin, Jr. A. (2016). Embracing followership: How to thrive in a leader-centric culture. Kirkdale Press. ISBN: 978-1-577996-32-3 |

| Heifetz, R., Grashow, A., & Linsky, M. (2010). The practice of adaptive leadership: Tools and tactics for changing your organization and the world. Personnel Psychology, 63(1), 255–258. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1744-6570.2009.01168_4.x |

| Hendrix, W. H., Born, D. H., & Hopkins, S. (2015). Relationship of transformational leadership and character with five organizational outcomes. Journal of Character and Leadership Integration, 3(1), 54–71. |

| Huang, T. (2020). A review of “Emotional Intelligence 2.0”: Travis Bradberry and Jean Greaves, San Diego, CA: Talent Smart (2009). Journal of Character and Leadership Development, 7(3), 108–109. |

| Hunter, J. E., Schmidt, F. L., & Judiesch, M. K. (1990). Individual differences in output variability as a function of job complexity. Journal of Applied Psychology, 75(1), 28–42. https://doi.org/10.1037/0021-9010.75.1.28 |

| Junker, N. M., & Van Dick, R. (2014). Implicit theories in organizational settings: A systematic review and research agenda of implicit leadership and followership theories. The Leadership Quarterly, 25(6), 1154–1173. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.leaqua.2014.09.002 |

| Kirkpatrick, S. A., & Locke, E. A. (1991). Leadership: Do traits matter? Executive, 5(2), 48–60. https://doi.org/10.5465/AME.1991.4274679 |

| Kolb, J. A. (1995). Leader behaviors affecting team performance: Similarities and differences between leader/member assessments. Journal of Business Communication, 32(3), 233–248. https://doi.org/10.1177/002194369503200302 |

| Koutsioumpa, E. M. (2023). Contribution of emotional intelligence to efficient leadership narrative review. Technium Social Sciences Journal, 48(1), 204–216. ISSN: 2668-7798 |

| Lawler, E. E. (2017). Reinventing talent management: Principles and practices for the new world of work. Berrett-Koehler Publishers. ISBN 978-1-5230-8250-6 |

| Lewis, P., Forsythe, G. B., Sweeney, P., Bartone, P. T., Bullis, C., & Snook, S. (2005). Identity development during the college years: Findings from the West Point longitudinal study. Journal of College Student Development, 46(4), 357–373. https://doi.org/10.1353/csd.2005.0037 |

| Liden, R. C., Wayne, S. J., Liao, C., & Meuser, J. D. (2014). Servant leadership and serving culture: Influence on individual and unit performance. Academy of Management Journal, 57(5), 1434–1452. https://doi.org/10.5465/amj.2013.0034 |

| Lindgren, B.-M., Lundman, B., & Graneheim, U. H. (2020). Abstraction and interpretation during the qualitative content analysis process. International Journal of Nursing Studies, 108, 103632. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijnurstu.2020.103632 |

| MAXQDA, Software for qualitative data analysis, 1989–2024, VERBI Software. Consult. Sozialforschung GmbH, Berlin, Germany. |

| Maxwell, J. C., & Dornan, J. (2006). The 360° leader: Developing your influence from anywhere in the organization. Thomas Nelson. ISBN 9781400203598. |

| Mayer, D. M., Aquino, K., Greenbaum, R. L., & Kuenzi, M. (2012). Who displays ethical leadership, and why does it matter? An examination of antecedents and consequences of ethical leadership. Academy of Management Journal, 55(1), 151–171. https://doi.org/10.5465/amj.2008.0276 |

| McCallum, J. S. (2013). Followership: The other side of leadership. Ivey Business Journal. https://iveybusinessjournal.com/publication/followership-the-other-side-of-leadership/ |

| Moon, S. H., Scullen, S. E., & Latham, G. P. (2016). Precarious curve ahead: The effects of forced distribution rating systems on job performance. Human Resource Management Review, 26(2), 166–179. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.hrmr.2015.12.002 |

| Mumford, M. D., Zaccaro, S. J., Connelly, M. S., & Marks, M. A. (2000). Leadership skills. The Leadership Quarterly, 11(1), 155–170. https://doi.org/10.1016/S1048-9843(99)00047-8 |

| Narin, F., & Breitzman, A. (1995). Inventive productivity. Research Policy, 24(4), 507–519. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0048-7333(94)00780-2 |

| Northouse, P. G. (2018). Leadership: Theory and practice (8th ed.). Sage Publications. ISBN 150636229X |

| Rainford, V. (2023). It’s time to retire the practice of forced distribution curves. Forbes Online. May 16, 2023. https://www.forbes.com/sites/forbeshumanresourcescouncil/2023/05/16/its-time-to-retire-the-practice-of-forced-distribution-curves/?sh=60a174153936 |

| Riggio, R. E., Chaleff, I., & Lipman-Blumen, J. (Eds.). (2008). The art of followership: How great followers create great leaders and organizations. Jossey-Bass. https://psycnet.apa.org/record/2008-01030-000 |

| Schleicher, D. J., Bull, R. A., & Green, S. G. (2009). Rater reactions to forced distribution rating systems. Journal of Management, 35(4), 899–927. https://doi.org/10.1177/0149206307312514 |

| Schraeder, M., & Simpson, J. (2006). How similarity and liking affect performance appraisals. The Journal for Quality and Participation, 29(1), 34. |

| Schyns, B., & Meindl, J. R. (Eds.). (2005). Implicit leadership theories: Essays and explorations. Information Age Publishing. ISBN 1-59311-361-7 |

| Slager, S. (2019, May 16). Followership: A valuable skill no one teaches. Forbes.com https://www.forbes.com/sites/forbesbostoncouncil/2019/05/16/followership-a-valuable-skill-no-one-teaches/ |

| Spain, E. S. (2020). Reinventing the leader-selection process: The US Army’s new approach to managing talent. Harvard Business Review. https://hbr.org/2020/11/reinventing-the-leader-selection-process |

| Spain, E., Matthew, K., & Hagemaster, A. (2022). Why senior officers sometimes fail in character: The leaky character reservoir. The US Army War College Quarterly: Parameters 53(4), 117–138. https://doi.org/10.55540/0031-1723.3190 |

| Spain, E., Mukunda, G., & Bates, A. (2021). The battalion commander effect. The US Army War College Quarterly: Parameters, 51(3), 101–114. https://doi.org/10.55540/0031-1723.3083 |

| Spears, L. C. (2010). Character and servant leadership: Ten characteristics of effective, caring leaders. The Journal of Virtues & Leadership, 1(1), 25–30. https://www.regent.edu/journal/journal-of-virtues-leadership/character-and-servant-leadership-ten-characteristics-of-effective-caring-leaders/ |

| Stewart, S. M., Gruys, M. L., & Storm, M. (2010). Forced distribution performance evaluation systems: Advantages, disadvantages and keys to implementation. Journal of Management & Organization, 16(1), 168–179. https://doi.org/10.5172/jmo.16.1.168 |

| Thorndike, E. L. (1920). A constant error in psychological ratings. Journal of Applied Psychology, 4(1), 25–29. https://doi.org/10.1037/h0071663 |

| Uhl-Bien, M., Riggio, R. E., Lowe, K. B., & Carsten, M. K. (2014). Followership theory: A review and research agenda. The Leadership Quarterly, 25(1), 83–104. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.leaqua.2013.11.007 |

| United States Army. (2019). Army Regulation 623-3, Evaluation reporting system, 14 June 2019. https://armypubs.army.mil/epubs/DR_pubs/DR_a/ARN14342-AR_623-3-000-WEB-1.pdf |

| United States Military Academy. (2018). Developing leaders of character: The West Point leadership development system. West Point. https://www.westpoint.edu/about/superintendent/governance-and-strategic-documents |

| United States Military Academy. (2022). Military program, academic year 2023. Department of Military Instruction, United States Corps of Cadets. |

| Williams, J. C., Loyd, D. L., Boginsky, M., & Armas-Edwards, F. (2021, April 24). How one company worked to root out bias from performance reviews. Harvard Business Review online. https://hbr.org/2021/04/how-one-company-worked-to-root-out-bias-from-performance-reviews |

| Witt, L. A., Burke, L. A., Barrick, M. R., & Mount, M. K. (2002). The interactive effects of conscientiousness and agreeableness on job performance. Journal of Applied Psychology, 87(1), 164. https://doi.org/10.1037/0021-9010.87.1.164 |

| Wortman, J., & Wood, D. (2011). The personality traits of liked people. Journal of Research in Personality, 45(6), 519–528. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jrp.2011.06.006 |

| Yukl, G. (2012). Effective leadership behavior: What we know and what questions need more attention. Academy of Management Perspectives, 26(4), 66–85. https://doi.org/10.5465/amp.2012.0088 |

| Yukl, G., & Van Fleet, D. D. (1992). Theory and research on leadership in organizations. In M. D. Dunnette & L. M. Hough (Eds.), Handbook of industrial and organizational psychology (2nd ed., pp. 147–197). Consulting Psychologists Press. http://ereserve.library.utah.edu/Annual/MGT/7800/SmithCrowe/theory.pdf |