PROGRAM/INTERVENTION

Distinguishing Types and Tiers of Self-Talk for Performance Enhancement

James Davis, Good Athlete Project

ABSTRACT

Self-talk refers to the dynamic narrative that is continually occurring between one’s ears. It plays a role in prediction, interpretation, instruction, motivation, communication, and making sense of one’s experience. Tuning in to this narrative, and working to deliberately cultivate it, plays an important role in performance. Those interested in leadership and character development should work to understand their own self-talk and the language they use to lead, as it will influence the self-talk of those in their charge. The more understanding one has over these principles, the better equipped they will be to match their inner narrative to their performance aims. This article takes a thorough look at types and tiers of self-talk to support leaders in their meaningful work.

Keywords: Self-Talk, Motivation, Leadership, Goal-Directed Behavior

Citation: Journal of Character & Leadership Development 2024, 11: 319 - http://dx.doi.org/10.58315/jcld.v11.319

Copyright: © 2024 The author(s). This is an Open Access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/), which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original work is properly cited.

CONTACT: James Davis jim@goodathleteproject.com

Published: 21 November 2024

Leadership and character development depend on communication. Providing direction, nurturing improvement, and building mental strength all rely, in large part, on the effective use of language. This includes the language we use inside our heads. The understanding and deliberate use of self-talk is an important component of this process.

Growth mindset is a familiar and prioritized capacity in character development, from classrooms to the United States Military Academy at Westpoint (Erbe et al., 2024). It describes the belief that improvement over time is possible, and that deliberate effort can positively influence one’s ability (Park et al., 2020; Yeager & Dweck, 2012). Developing a growth mindset depends on a leader framing situations and outcomes for those in their charge. When feedback is delivered in a way that highlights talent or fixed abilities, for example, learners engage with challenges differently (and less effectively) than when learners are praised for their work ethic and approach to problems (Dweck & Yeager, 2019). One possible mechanism for this impact is the cultivation of inner dialogue through external direction; that is, the language used by the instructor cues internal language used by the learner.

When one is consistently praised for their talent, inner narratives might reflect a connection to a fixed ability: for example, “I am smart.” When that person encounters a setback their inner dialogue can shift, “maybe I’m not as smart as I thought.” Self-talk reflecting this sort of “fixed” mindset is not ideal. Instead, a leader should use language focused on process, approach and work ethic. They will remind those in their charge that, despite challenges, they have an opportunity for growth. Direction using this sort of language has the potential to cultivate empowering inner narratives in others. One who has developed an inner narrative focused on growth might encounter a setback and think, “I missed the mark, but I can work hard and adjust.” These internal narratives can signal and cultivate mental models, which are an essential component of the decision-making process and ultimately, behaviors (Mattar & Lengyel, 2022).

Deliberate use of self-talk has been linked to improvements in emotion regulation, performance, and alterations in neurological activation (Alfermann, 2019; Orvell & Kross, 2019; Walter et al, 2021). By unbraiding internal narratives, shining a light on effective self-talk strategies, as well as limiting ineffective or degrading forms of self-talk, a practitioner can gain personal insight, change the way they think, and better support people who are trying to do the same.

Self-talk is essential to character and leadership development. Coaches, educators, and leaders of all kinds should focus on self-talk to (1) gain control over their own inner-dialogue, and (2) support effective use of self-talk in those they lead.

Understanding Self-Talk

Thoughts influence behaviors, behaviors create outcomes, outcomes are interpreted through the filter of thoughts (internal processes and narratives). It is a continuous process. While many other factors are at play, including emotion and physiology, gaining control over one’s inner narrative offers an opportunity to enhance one’s state, behaviors, and outcomes… and support those they lead through a similar process.

Imagine a coach in a highly contested football game. If the coach’s self-talk throughout the game includes ruminating on negative external components of the game (like weather conditions and contestable calls by a referee), that will impact his behavior. When a ref makes a “bad” call, the coach’s disgruntled reaction, which was predisposed by his inner narrative, will deliver a message to those around him and further entrench his negative state. After the game, he might suggest that “those refs really screwed us,” installing that narrative in the minds of his players.

This approach does not serve the coach, and it creates a ripple effect in the team. The athletes might then talk among themselves about how bad the refs were. When a friend asks how the game went, they might point directly to the refs, who “screwed us.” The internal dialogue that flows from that point leaves the athlete with nothing to work on – after all, it was not their fault, it was the referee. That externally focused, negative self-talk will impact future behaviors. How would an athlete go on to practice in a way that accounts for a bad referee?

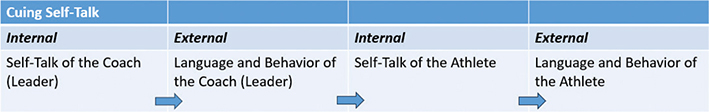

Those aiming for character and leadership development should know that by modeling a specific sort of language and approach, leaders are cuing self-talk in those they lead. Internal dialogue used by the leader can manifest in the external language a leader uses around their people, which influences the sort of inner narratives of those being led (Astington, 1999; Vygotsky, 1962; Zlatev & Blomberg, 2015). We developed this progressive visual aid to use with leaders (Figure 1) in order to improve usability of this concept. A leader has the opportunity to recognize where, within this chain of events, they are experiencing a concern, in order to properly identify next steps.

Figure 1

The Progression of Leaders Cuing Self-Talk in Athletes

For example, the football coach might want to gain control over his inner dialogue and use language that recognizes the fact that a few calls did not go his team’s way, but there were moments during the game that were under the team’s control. He could, through his use of language, install a narrative that allows his team to focus on those controllable moments. This, instead of a default position influenced by negative perception of external forces, the coach and athletes would have agency.

Developing agency can lead to empowerment. Self-talk is an essential tool in well-studied character development capacities like growth mindset, grit, and emotion regulation (Duckworth & Gross, 2014; Dweck & Yeager, 2019; Moser et al, 2017). If a leader can enhance or degrade those abilities in their people through the language they use, they should.

Think of the categories below as tools in the toolkit of one’s mind. As projects arise, it is good to know (1) that you have tools at your disposal, (2) what those tools are and what they are capable of, and (3) how to gain experience using and cultivating those tools for future use. Many of the skills taught in cognitive behavioral therapy, dialectical behavioral therapy, and performance psychology depend on the awareness and intentional use of such internal tools (Brinthaupt & Morin, 2023; Hardy et al, 2009; Schaich et al, 2021). The most effective form of self-talk depends on multiple variables including situational context, task, and the state of the user. For example, motivational self-talk, as described below, is most appropriate when motivation is lacking. If one is already in a state of physical and psychological arousal, more motivation is not likely to be effective (Theodorakis, 2000). The Yerkes-Dodson Law proposes that the increase in arousal beyond optimal level can be counterproductive (Yerkes & Dodson, 1908). Understanding the nuances of self-talk can better equip one with appropriate tolls of the task at hand. With awareness, understanding, and tools at their disposal, a leader has an opportunity to be more intentional in their approach.

All good decision making is preceded by understanding. The first step is any intentional leadership is awareness; that is, bringing awareness to the fact that their inner dialogue is running. The second step is understanding. Understanding the influence of self-talk on behavior is essential. The dedicated leader will go one step further, as heightened understanding includes the recognition of types and tiers, as discussed in this article.

Types of Self-Talk

Allyson Felix, 9-time Track & Field medalist, has made a habit of talking to herself. At the starting line before a big race, she will say things to herself like, “let’s do this, it’s time.” Elite athletes tend to their bodies and minds. There is an increasing awareness of the impact of self-talk on athletic performance across a variety of sports (Hatzigeorgiadis et al, 2011; Santos-Rosa et al, 2022; Theodorakis et al, 2000).

Just before competition, Felix’s self-talk has a certain flavor. She is not thinking about posture or stride length, she is hyping herself up (“let’s do this”). Different types of self-talk – such as positive, negative, instructional, or motivational – work better in certain situations than others. Building an understanding of types and, as expanded on in this article, tiers of self-talk is an important step in maximizing its effect on performance.

There are many “types” of self-talk. A type refers to a category of self-talk with common characteristics. Positive and negative self-talk appear to be the most familiar. Research and practical applications continue to identify the importance of cultivating an inner narrative in service of life-satisfaction and performance (Mamak, 2019). Familiar examples note the ability of an inner narrative to influence expectations around specific events. If an athlete were to enter a game with self-doubt, “I stink” or “I don’t know if I can do this,” he changes the way he engages with the obstacle (the opponent over the course of the game). Every missed shot would be confirmation of this negative, self-effacing inner narrative. Conversely, positive self-talk like “I can do this” or “I practiced hard and I’m ready” might positively influence the way he engages with the same opponent. There again, studies in confirmation bias would suggest that every made shot in this case was proof of ability, and perhaps the missed shots could be seen as opportunities to adjust strategy instead of suggesting that he “stinks” (Nickerson, 1998).

Beyond positive and negative self-talk, Theodorakis and others have identified two additional types: instructional and motivational self-talk. Instructional self-talk includes cues which guide performance, such as foot placement or positioning in a drill. Motivational self-talk is more generalized, often offering internal encouragement like “I got this” or “I’m ready, let’s go.” Each plays a role in performance and has most commonly been studied in athletes (Theodorakis et al, 2000).

It is important for leaders to recognize this difference. If a coach continues to motivate without giving sufficient instruction, their team might find themselves incredibly amped up, but lacking understanding of what to do or how to do it. This can happen in the opposite direction as well. There are plenty of instances where an athlete knows exactly what to do, as the instruction has been incredibly thorough, but there is not enough excitement to accomplish the task amid challenging circumstances.

There must be balance. Instructional self-talk might be better suited for training, or while prepping for a competition. Motivational might fit best when the athlete is confident in the assignment and task, but wants to overcome self-doubt with a motivational reminder. Their usage might shift throughout a training session depending on the nature of a drill or task. Recognizing these types of self-talk enhances the opportunity for strategic and effective usage.

Tiers of Self-Talk

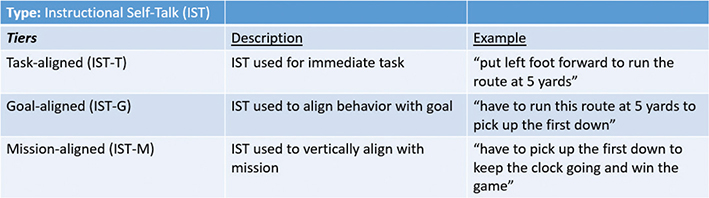

Positive and negative, instructional and motivational – these are categories which encompass the primary types of self-talked used before, during, and after performance. Significant experience and motivational interviewing of championship teams and leaders across multiple professional domains has revealed that there are “tiers” of self-talk occurring within these types. While conducting a recent round of research on self-talk in coaches, Dr. David Cutton (Texas A&M University Kingsville) found these tiers continued to present themselves. A tier refers to the relative arrangement of self-talk within the broader type. Understanding the tiers within well-studied types of self-talk can further codify and evaluate use of self-talk within the leader, and support the leader in training that inner dialogue within those they have been tasked to lead. While this is not an exhaustive list, it identifies common variations (as shown in Figure 2).

Figure 2

Tiers of Instructional Self-Talk

Task-Aligned Instructional Self Talk (IST-T)

Task-aligned indicates that the instructional self-talk is being used for the immediate task at hand. A wide receiver might internally remind himself to put his left foot forward in his stance, focus on the hands of the defensive back to avoid a “press” off the line, and sink his hips to adjust his route at 5 yards. This internal dialogue aligns directly with the task of running his route. In a different situation, a professor about to leave her home for travel might remind herself to turn down the thermostat to 70 degrees, then tie up the garbage and set it by the door so she remembers to take it out before she heads off to the airport. These in-moment reminders or internal directives allow conscious accomplishment (and adjustment, as needed) of the current task.

Goal-Aligned Instructional Self Talk (IST-G)

This sort of self-talk requires an identification of a slightly larger goal for which someone is performing a given task. A wide receiver might remind himself that, on 3rd and 4th, he must run his route beyond 4 yards to pick up the first down. The goal is the first down; he can then use task-aligned self-talk in accordance with that goal. The traveling professor might remind herself that she will not be home for a week and wants her apartment to be prepared for that time; she does not want to waste energy heating an empty apartment and does not want the garbage to stink up the kitchen in her absence. An internal reminder of the goal can enhance the use of task-aligned instructional self-talk to accomplish those goals by creating a congruency with a larger goal.

Mission-Aligned Instructional Self Talk (IST-M)

This layer of self-talk includes identification and occasional reminders of the overarching mission. The receiver’s mission is to win the game, his next goal is to help his team pick up the first down, and his left foot must be forward so his task of running a 5-yard route can be accomplished. The professor’s mission might be to have a successful trip to a conference at which she is presenting, she wants to relieve her subconscious of worrying about whether or not her house is in order, she then focuses on the tasks of turning down the thermostat and taking out the garbage. While using IST-M, one has an opportunity to vertically align their decision-making and inner narrative. Without internal reminders of the mission, goal- and task-aligned self-talk might not be easy to identify or utilize. When those tasks become challenging (the receiver is exhausted in the fourth quarter or the traveler is up at 4:00am to make an early flight), the mundane tasks can feel heavier if they are not clearly aligned with the larger mission. Using IST-M creates congruency and gives purpose to tasks.

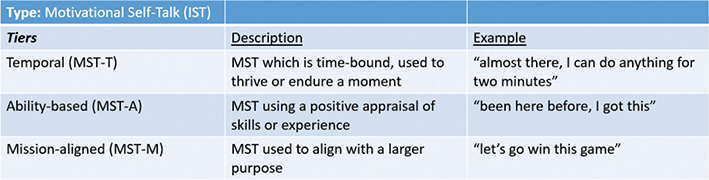

Motivational Self-Talk can influence one’s physiological state. Cutton identified the use of intense self-talk used by an elite powerlifter to enhance his performance in competition, noting that he could enhance access to his existing physical ability through directed inner-narrative (Cutton & Hearon, 2014). Other studies have associated this style of self-talk with differentiated activation of neural networks, suggesting that types of self-talk impact not only outcomes, but distinct activity in the brain (Kim et al, 2021). As with IST, MST can also appear in tiers, as shown in Figure 3.

Figure 3

Tiers of Motivational Self-Talk

Temporal Motivational Self-Talk (MST-T)

This is often time bound and used to thrive or endure in a moment. The receiver trying to perform at a high-level in a state of near-exhaustion might use self-talk like, “only two minutes left in the game, I can do anything for two minutes; one play at a time.” The traveler who is working on her presentation during the flight suddenly has computer issues might say, “only an hour left in the flight, I’ll use a notepad until then and transfer when I get to the hotel, I can get adjust for an hour.” Athletes will often include time constraints to manage the intensity of the moment and appraise the degree of difficulty. In training sessions, one might use temporal self-talk to hold a difficult plank position for “10 more seconds” instead of enduring the discomfort for an abstract, unidentified length of time. During difficult preseason practices, an athlete might remind themselves that there are “only two more days” to remind themselves that there is a rest in sight, thereby committing fully to the next stretch of time. One might also use time constraints in the opposite direction, noting after an early loss that “it’s a long season” and there is time to improve. This strategy depressurizes the moment and allows for more thoughtful appraisal, instructional self-talk, and deliberate work toward a future goal.

Ability-Based Motivational Self-Talk (MST-A)

This style of self-talk is generally optimistic in nature and often includes positive appraisal of skills. Each of the MST-T examples above used an element of MST-A. When pushing through the final 2-min of a game, the receiver reminds himself that he can get through the next stretch of time by because he “can do anything for two minutes.” The traveling professor reminds herself that, for the next hour, she is confident in her ability to adjust. These levels of self-talk often work in concert, though they do not have to. MST-A can be far broader, appearing in the form of “let’s go,” “we got this,” or “nobody can stop us.” Allyson Felix confidently went with “let’s do this, it’s time.” MST-A appears to be the most common form of Motivational Self-Talk.

Mission-Aligned Motivational Self-Talk (MST-M)

Similar to Mission-aligned Instructional Self-Talk, this often serves as a reminder of the larger purpose for sake of motivation. It appears in forms like “let’s go, we have a game to win.” In the professor, it might take the form of “this presentation is going to be valuable to people, I got this, I am going to adjust as needed to make sure it happens, and happens well.” Aligning the moment with its larger, deeper purpose can imbue it with a resonance that pushes performance to a higher level. This is distinguishable from Mission-aligned Instructional Self-Talk (IST-M) to the degree that it pulls in emotion rather than cognition; that is, the more the emotion-driven alignment with a professor’s purpose when saying “this is going to be valuable, I got this,” compared to the cognitive vertical alignment of wanting to free herself from worry so that she can concentrate on her mission of educating people at the conference. Regarding MST-M, it is not uncommon to hear an Olympic medalist on the podium reflecting that they “did it for my parents, who always supported me,” or “I wanted to make my country proud,” or “thanks to God for making this possible.” When that inner narrative is folded into one’s self-talk, they often find it possible to push a little farther, work a little harder, and continue in service of the mission.

Stacking Self-Talk

Self-talk rarely falls strictly into one of these categories. One might need Motivational self-talk to get themselves to a place where Instructional self-talk is possible. They might move up and down the tiers and across types. They might bump into a negative line of thought, recognize it, and use Instructional self-talk to get themselves back into positive language (using self-talk to guide future self-talk). The receiver might be in the midst of task-aligned instructional self-talk, feel exhaustion set in, then use mission-aligned motivational self-talk to get back to a place where they can again focus on the task.

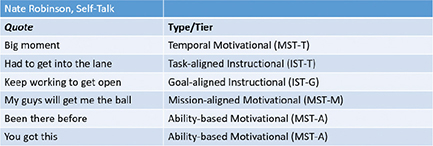

Nate Robinson spent 10 years in the NBA. He was a guest on the Good Athlete Podcast (Episode 29) and revealed numerous insights into his self-talk. At one point he reflected on one of his clutch performances with the Chicago Bulls, during the 2013 playoffs.

“That was a big moment for us. I just knew I had to get into the lane and keep working to get open and my guys would get me the ball,” he said, followed by “I been there before, I just said to myself ‘you got this’” (personal communication, 2019).

Robinson was stacking self-talk. Decades of playing gave him a high level of awareness in this realm and he easily shifted through types and tiers to create an effective inner narrative and, ultimately, an ideal performance state.

An examination of Robinson’s self-talk:

Robinson, like many athletes, demonstrates that while in the moment, he inched closer and closer to Motivational styles. He understood the importance of the moment as it aligned with the team mission. He brought awareness to his task (getting to the lane, working to get open), and punctuated the moment with Motivation (you got this).

There is no precise script for how self-talk should be used. Golfers often include the use of positive and neutral self-talk to limit arousal (Marshall et al, 2016), whereas Cutton’s powerlifter example used self-talk to enhance arousal (Cutton & Hearon, 2014). Increased awareness of types and tiers – and a recognition of what works best in a personalized, context-specific way – can turn the running dialogue between one’s ears into an understandable landscape, and bring awareness to the tools at their disposal. It can help codify and evaluate effectiveness of self-talk strategies.

Awareness and understanding always precede responsible decision making. The ability to distinguish types and tiers of self-talk can provide agency through a newfound ownership of that talk.

Self-Talk Across Domains

Since language is an essential component of character and leadership development, exceptional leaders should work to become experts. While there are obvious applications in the field of mental health, leadership development, and performance enhancement, cultivating self-talk is valuable in all areas.

Imagine a scenario where you work with “Steve.” Steve is a team member who you have had mostly positive interactions with, who you believe to be a good guy, but who rubbed you the wrong was in a recent meeting. If, between interactions with Steve, your self-talk could be characterized as negative, evaluating all the ways Steve “wronged” you, ruminating on all of Steve’s faults, internally referring to Steve as a “dope” and a “fool” who does not understand you or respect your time – imagine how your next interaction with Steve might go. Future interactions with Steve might be nudged by the filter you have put on the situation, the narrative by which you describe him, resulting in a set of behaviors and interactions aligning with this inner narrative. On the other hand, if your self-talk is positive, optimistic, willing to give Steve the benefit of the doubt, and refers to Steve as a good guy who may have made a misstep, but you remind yourself that you are on the same team and willing to work with him to right the ship – image how differently that next interaction might unfold. In the development of leadership and character, even for those who are hoping to move quickly, it is worth slowing down and developing a fuller picture of the landscape. Best laid plans are effective only if knowledge inputs are current.

Whether it is in the workplace, the classroom, the court, or on the track, a leader can gain personal insight, change the way they think, and better support people who are trying to do the same by using effective self-talk. Understanding types and tiers is an important step in that process. Further articles should examine the additional types and tiers of self-talk, including but not limited to third-person self-talk, filtering, and catastrophizing. In any case, it begins with awareness. As Felix noted, one ought to be present in the moment, bring awareness to their inner narrative, and gain control over those thoughts. From there, a leader can create opportunities for performance enhancement and develop character that lasts a lifetime.

References

| Astington, J. W., & Jenkins, J. M. (1999). A longitudinal study of the relation between language and theory-of-mind development. Developmental Psychology, 35, 1211–1320. https://doi.org/10.1037/0012-1649.35.5.1311 |

| Brinthaupt, T. M., & Morin, A. (2023). Self-talk: Research challenges and opportunities. Frontiers in Psychology, 14, 1210960. https://doi.org/10.3389/fpsyg.2023.1210960 |

| Cutton, D. M., & Hearon, C. M. (2014). Self-talk functions: Portrayal of an elite power lifter. Perceptual and Motor Skills, 119(2), 478–494. https://doi.org/10.2466/29.PMS.119c25z2 |

| Duckworth, A., & Gross, J. J. (2014). Self-control and grit: Related but separable determinants of success. Current Directions in Psychological Science, 23(5), 319–325. https://doi.org/10.1177/0963721414541462 |

| Dweck, C. S., & Yeager, D. S. (2019). Mindsets: A view from two eras. Perspectives on Psychological Science, 14(3), 481–496. https://doi.org/10.1177/1745691618804166 |

| Erbe, R., Konheim-Kalkstein, Y., Fredrick, R., Dykhuis, E., & Meindl, P. (2024). Designing a course for lifelong, self-directed character growth. Journal of Character & Leadership Development, 11(286), 1–11. https://doi.org/10.58315/jcld.v11.286 |

| Hardy, J., Oliver, E., & Tod, D. (2009). A framework for the study and application of self-talk within sport. In S. D. Mellalieu & S. Hanton (Eds.), Advances in applied sport psychology (pp. 37–74). Routledge/Taylor & Francis Group. |

| Hatzigeorgiadis, A., Zourbanos, N., Galanis, E., & Theodorakis, Y. (2011). Self-talk and sports performance: A meta-analysis. Perspectives on Psychological Science, 6(4), 348–56. https://doi.org/10.1177/1745691611413136 |

| Kim, J., Kwon, J. H., Kim, J., Kim, E. J., Kim, H. E., Kyeong, S., & Kim, J. J. (2021). The effects of positive or negative self-talk on the alteration of brain functional connectivity by performing cognitive tasks. Scientific Reports, 11(1), 14873. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-021-94328-9 |

| Mamak, H. (2019). The determinant effect of self-talk status of athletes on life satisfaction. Journal of Education and Learning, 8(4), 161–168. https://doi.org/10.5539/jel.v8n4p161 |

| Marshall, D. V. J., Hanrahan, S. J., Comoutos, N. (2016). The effects of self-talk cues on the putting performance of golfers susceptible to detrimental putting performances under high pressure settings. International Journal of Golf Science, 5, 116–134. https://doi.org/10.1123/ijgs.2016-0001 |

| Mattar, M. G., & Lengyel, M. (2022). Planning in the brain. Neuron, 110(6), 914–934. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.neuron.2021.12.018 |

| Moser, J. S., Dougherty, A., Mattson, W. I. et al. (2017). Third-person self-talk facilitates emotion regulation without engaging cognitive control: Converging evidence from ERP and fMRI. Scientific Reports, 7, 4519. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-017-04047-3 |

| Nickerson, R. S. (1998). Confirmation bias: A ubiquitous phenomenon in many guises. Review of General Psychology, 2(2), 175–220. https://doi.org/10.1037/1089-2680.2.2.175 |

| Orvell, A., & Kross, E. (2019). How self-talk promotes self-regulation: Implications for coping with emotional pain. In C. Rudert, R. Greifeneder, K.D. Williams (Eds.), Current directions in ostracism, social exclusion, and rejection research (pp. 82–99). Routledge/Taylor & Francis Group. |

| Park, D., Tsukayama, E., Yu, A., & Duckworth, A. L. (2020). The development of grit and growth mindset during adolescence. Journal of Experimental Child Psychology, 198, 104889. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jecp.2020.104889 |

| Santos-Rosa, F. J., Montero-Carretero, C., Gómez-Landero, L. A., Torregrossa, M., & Cervelló, E. (2022). Positive and negative spontaneous self-talk and performance in gymnastics: The role of contextual, personal and situational factors. PLoS One, 17(3), e0265809. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0265809 |

| Schaich, A., Braakmann, D., Rogg, M., Meine, C., Ambrosch, J., Assmann, N., Borgwardt, S., Schwiger, U., & Fasbinder, E. (2021). How do patients with borderline personality disorder experience Distress Tolerance Skills in the context of dialectical behavioral therapy? – A qualitative study. PLoS One, 16(6), e0252403. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0252403 |

| Theodorakis, Y., Weinberg, R., Natsis, P., Douma, I., & Kazakas, P. (2000). The effects of motivational versus instructional self-talk on improving motor performance. The Sport Psychologist, 14(3), 253–271. https://doi.org/10.1123/tsp.14.3.253 |

| Vygotsky, L. S. (1962). Thought and language. MIT Press. |

| Walter, N., Nikoleizig, L., & Alfermann, D. (2019). Effects of self-talk training on competitive anxiety, self-efficacy, volitional skills, and performance: An intervention study with junior sub-elite athletes. Sports (Basel), 7(6), 148. https://doi.org/10.3390/sports7060148 |

| Yeager, D. S., & Dweck, C. S. (2012). Mindsets that promote resilience: When students believe that personal characteristics can be developed. Educational Psychologist, 47(4), 302–314. https://doi.org/10.1080/00461520.2012.722805 |

| Yerkes, R.M.D., & Dodson, J.D. (1908). The relation of strength of stimulus to rapidity of habit formation. J Comp Neurol Psychol 18, 459–482. |

| Zlatev, J., & Blomberg, J. (2015). Language may indeed influence thought. Frontiers in Psychology, 6, 1631. https://doi.org/10.3389/fpsyg.2015.01631 |